1. Introduction: A Shift in Understanding Criminal Behavior

For decades, criminologists have sought to answer a fundamental question: Why do people commit crimes? Early explanations often focused on biological determinism or the idea that criminal behavior stems from innate traits or physical abnormalities. The Classical School, with figures like Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, emphasized rational choice, positing that people weigh costs and benefits before engaging in unlawful acts. While these theories laid important foundations, they did not fully account for the social and psychological complexity of human behavior.

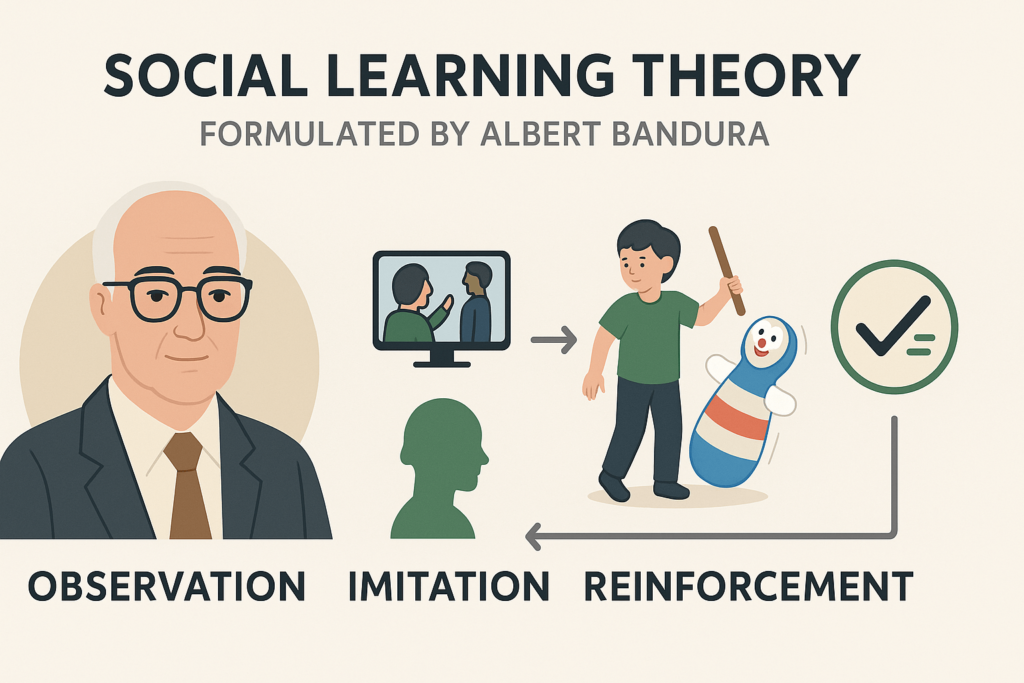

As research evolved, scholars began to recognize that crime often occurs within social contexts. It became increasingly clear that individuals are influenced by their environment—particularly by the people around them. This shift in focus led to the development of theories that considered the social processes through which behavior is learned. One of the most influential of these is Social Learning Theory, which emphasizes that individuals acquire behaviors through observation, imitation, and interaction with others.

In criminology, Social Learning Theory offers a valuable framework for understanding how criminal tendencies are not merely chosen or biologically determined but are often learned over time through repeated social exposure. This perspective has reshaped how scholars approach crime prevention, moving from punitive responses to strategies that focus on education, mentorship, and community support.

2. Albert Bandura: The Mind Behind Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura, a Canadian-American psychologist, is widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers in behavioral science. His groundbreaking contributions began in the 1960s when he introduced the idea that human learning is largely shaped by observation and imitation. Bandura proposed that people do not need to experience consequences firsthand to learn behavior; instead, they can learn by watching others and observing the outcomes of their actions.

Bandura’s famous “Bobo doll” experiment illustrated this concept vividly. In the study, children who observed adults behaving aggressively toward an inflatable doll were more likely to replicate that aggression, even without receiving any direct reward or punishment. This finding challenged the behaviorist view that learning only occurs through reinforcement, and it laid the foundation for a broader theory of observational learning.

Throughout his career, Bandura continued to refine his ideas. He later introduced the concept of self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform specific actions. This addition made Social Learning Theory even more applicable to areas like motivation, behavior change, and personal responsibility. Bandura’s legacy extends far beyond psychology—his theories have significantly influenced education, communication, and particularly criminology, where understanding how criminal behavior is modeled and learned remains a central concern.

3. The Core of Social Learning Theory: Bandura’s Contributions

At the heart of Social Learning Theory are four cognitive and behavioral processes: attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. First, individuals must pay attention to a behavior being modeled. If the model is perceived as credible, powerful, or similar to the observer, the behavior is more likely to be noticed. Second, the behavior must be retained in memory—this involves encoding and storing the observed actions for future replication.

Third, reproduction refers to the individual’s ability to perform the observed behavior. This depends on both physical capability and psychological readiness. Finally, motivation plays a critical role. People are more likely to imitate behavior if they see it rewarded or if they believe it will lead to positive outcomes. These principles help explain why certain individuals engage in criminal acts after observing others, particularly when such acts appear to be beneficial or socially accepted within their peer group.

In criminological settings, these processes are evident in how young people may learn to steal, fight, or use drugs by observing friends or family members who engage in such behaviors without facing negative consequences. When the behavior is reinforced—through peer approval, financial gain, or elevated social status—it becomes more deeply embedded. Bandura’s model provides a comprehensive explanation for how criminal behavior spreads within communities and across generations.

4. The Influence of Albert Bandura on Other Criminological Theories

Bandura’s work significantly influenced other major theories in criminology, particularly those that also emphasize learning and social influence. One of the earliest theories to align with Bandura’s ideas was Edwin Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory, which posits that criminal behavior is learned through interactions with others who hold favorable attitudes toward crime. Bandura built upon this by explaining the mechanisms of learning, offering insight into how criminal attitudes are adopted through observation and imitation.

Another theory impacted by Bandura is Cognitive Behavioral Theory, which combines elements of cognitive psychology and behaviorism to explain deviance. Bandura’s emphasis on internal mental processes such as self-efficacy and moral disengagement directly contributed to the development of cognitive-behavioral strategies used in offender rehabilitation. These programs help offenders reframe their thinking, reduce impulsivity, and develop prosocial behavior—goals that align closely with Social Learning Theory principles.

Bandura’s insights also intersect with Labeling Theory, particularly in the way individuals internalize societal reactions and adjust their behavior accordingly. When people observe how others are treated after committing crimes—whether stigmatized or glamorized—they may model their own actions accordingly. Through this lens, Social Learning Theory enhances our understanding of how societal reactions and observed consequences shape criminal trajectories.

5. Ronald Akers and the Integration of Reinforcement

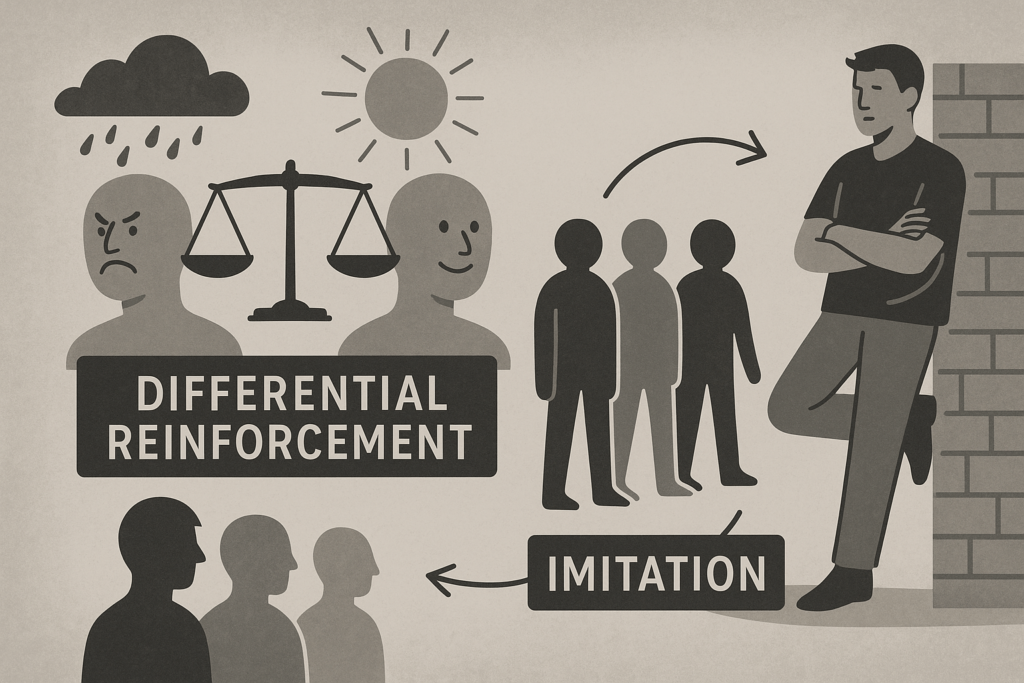

Ronald Akers, a leading criminologist, expanded upon Bandura’s theory by integrating it with behaviorist principles to form a criminology-specific version known as Social Structure and Social Learning Theory (SSSL). Akers introduced the concept of differential reinforcement, which asserts that behaviors are maintained or diminished based on the social rewards or punishments they receive. This idea complemented Bandura’s focus on observational learning by emphasizing the consequences that reinforce or discourage behavior.

Akers’ model also incorporated imitation, definitions, and differential association into a more structured framework. “Definitions” refer to an individual’s attitudes or moral beliefs about certain behaviors. When a person is surrounded by peers or role models who support criminal behavior, they may adopt favorable definitions toward those actions, increasing the likelihood of imitation. Reinforcement then plays a key role in maintaining the behavior once it has been learned.

This model has been especially effective in explaining delinquent behavior among adolescents, where peer approval, group dynamics, and reinforcement are highly influential. From drug use to gang activity, Akers’ version of Social Learning Theory provides a robust explanation for how behavior is acquired, sustained, and even escalated through continued social reinforcement and environmental feedback.

6. Applications of Social Learning Theory in Juvenile Delinquency Prevention

One of the most practical applications of Social Learning Theory is in preventing juvenile delinquency. Adolescents are especially impressionable and often model their behavior after peers, parents, or media figures. Understanding how social environments influence behavior helps educators, social workers, and criminal justice professionals design interventions that replace negative models with positive ones. Mentorship programs, for example, pair at-risk youth with adults who exhibit prosocial behavior and encourage goal setting, empathy, and self-control.

School-based initiatives have also adopted Social Learning Theory principles by promoting peer-led activities that reward cooperation, nonviolence, and academic engagement. These programs often include conflict resolution workshops, social skills training, and structured extracurricular activities. By providing adolescents with models of constructive behavior and immediate positive reinforcement, such interventions reduce the appeal and influence of deviant peer groups.

Moreover, community-based programs informed by Social Learning Theory seek to transform the environments that foster criminal behavior. Efforts such as neighborhood revitalization, parent training programs, and youth clubs aim to reshape the broader social context, reducing exposure to crime and increasing access to supportive role models. This approach recognizes that crime prevention is not just about removing negative influences but about actively promoting healthier social learning opportunities.

7. The Role of Media and Technology in Modern Social Learning

In today’s digital age, the mechanisms described by Social Learning Theory are more relevant than ever. The internet, social media, video games, and streaming platforms provide constant exposure to behaviors—both positive and negative—modeled by others. Bandura’s theory helps explain how indirect modeling, or symbolic modeling, can influence behavior even in the absence of direct interaction. For example, repeated exposure to violent video games or aggressive influencers may normalize these behaviors for young viewers.

This modeling becomes especially concerning when criminal acts are portrayed as glamorous or without consequence. Whether it’s theft in a viral prank video or aggression in a popular film, these depictions can subtly teach observers that such behaviors are acceptable or even rewarded. Research shows that individuals—especially adolescents—who consume large volumes of violent or antisocial media are more likely to display similar behaviors themselves.

However, Social Learning Theory also highlights the positive role media can play. Educational content, social campaigns promoting anti-bullying or civic engagement, and visibility of positive role models can all foster prosocial learning. When designed thoughtfully, media can be a powerful tool for shaping values, encouraging empathy, and deterring criminal behavior. Thus, the theory offers not just critique but also a roadmap for more ethical and constructive use of technology in shaping behavior.

8. Comparing Social Learning Theory to Other Criminological Schools

When placed alongside other criminological theories, Social Learning Theory stands out for its balanced integration of psychological and social factors. Unlike the Classical School, which sees individuals as rational actors making calculated decisions, Social Learning Theory posits that behavior often stems from unconscious imitation and social reinforcement, not just cost-benefit analysis. This view provides a more nuanced explanation for impulsive or emotionally driven crimes.

The Biological School attributes criminality to inherited traits, neurological conditions, or physiological factors, often neglecting the role of social interaction. While these approaches may help explain predispositions, they cannot fully account for the social context in which behaviors are learned. Social Learning Theory fills this gap by focusing on the environment and social cues that shape individual choices.

Moreover, Social Learning Theory complements and expands on theories such as Strain Theory, which argues that individuals turn to crime when they lack legitimate means to achieve societal goals. While Strain Theory explains motivation, it doesn’t clarify how criminal methods are learned. Social Learning Theory steps in to explain the learning process, demonstrating how individuals acquire techniques, justifications, and attitudes supportive of crime by observing others.

9. Criticisms and Limitations of Social Learning Theory in Criminology

Despite its widespread influence, Social Learning Theory is not without criticism. One of the main challenges lies in its inability to explain individual variability in response to similar environments. For example, two children raised in the same neighborhood and exposed to the same models of behavior may take completely different paths—one becoming law-abiding, the other delinquent. Critics argue that the theory downplays the role of personal choice, biological predispositions, or internal moral frameworks.

Another criticism centers around measurement difficulties. Observational learning is inherently subjective, making it difficult to quantify in empirical research. While Bandura’s original experiments were controlled and replicable, applying the theory to real-world crime scenarios presents methodological limitations. Researchers often struggle to isolate modeling as the sole influence, since behavior results from a complex interplay of factors.

Additionally, some argue that the theory may oversimplify the causes of crime by focusing heavily on social exposure. It may neglect macro-level influences such as economic inequality, systemic racism, or political instability, which also contribute to criminal behavior. As a result, many scholars advocate for integrative models that combine Social Learning Theory with biological, cognitive, and structural approaches for a more comprehensive understanding.

10. Conclusion: The Enduring Impact of Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura‘s Social Learning Theory has transformed how we understand learning, behavior, and criminality. By introducing the idea that individuals learn from observing and imitating others, he provided a powerful framework that continues to shape criminal justice policy, educational programming, and psychological research. The theory has inspired interventions ranging from school mentorship programs to community rehabilitation efforts, proving its practical value in real-world settings.

Through extensions by thinkers like Ronald Akers, Social Learning Theory has evolved into a cornerstone of modern criminology. It offers a dynamic lens through which to view crime—not as a fixed trait, but as a learned response to one’s social environment. This view opens up new possibilities for prevention, suggesting that changing what people see and experience can ultimately change how they behave.

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected through technology and media, the core principles of Social Learning Theory remain more relevant than ever. Whether through in-person relationships or online interactions, the models we observe continue to shape who we are and how we act. Bandura’s legacy endures as a guiding light for understanding not only crime but also the immense power of social influence in shaping human behavior.