Introduction

Deviance remains one of the most crucial topics in criminology and sociology. It provides insight into why individuals engage in behaviors that society deems unacceptable, how such behaviors develop over time, and how individuals and groups are labeled and treated as a result. One of the most influential contributions to the understanding of deviance comes from Edwin Lemert, who introduced the concepts of primary and secondary deviance. These two categories help distinguish between an initial, often incidental rule-breaking act and a more entrenched pattern of behavior shaped by social reactions.

This paper seeks to examine the theory of primary and secondary deviance from a criminological perspective, offering a thorough exploration of its definitions, theoretical background, causes, case studies, social and identity-related consequences, and its implications for the justice system. Furthermore, the paper will explore the theory’s criticisms and its place within contemporary criminological thought. By the end, the reader will have a comprehensive understanding of how deviant behavior develops, evolves, and is either managed or reinforced through societal mechanisms.

1. Definitions and Key Concepts

1.1. What Is Deviance?

Deviance is commonly defined as behavior that violates social norms. These norms can be formal—like laws—or informal, such as cultural expectations and moral standards. What is considered deviant in one society might be normal or even celebrated in another. For example, behaviors such as public nudity, drug use, or aggressive political dissent may be considered deviant depending on the context and culture.

In criminology, deviance overlaps with crime, but the two are not synonymous. All crimes are technically deviant because they violate laws, but not all deviant acts are criminal. For instance, extreme body modifications or unconventional lifestyles may be seen as deviant but are not illegal.

Understanding deviance thus requires an awareness of the fluidity of social norms, the role of power in defining deviance, and the mechanisms through which societies enforce conformity.

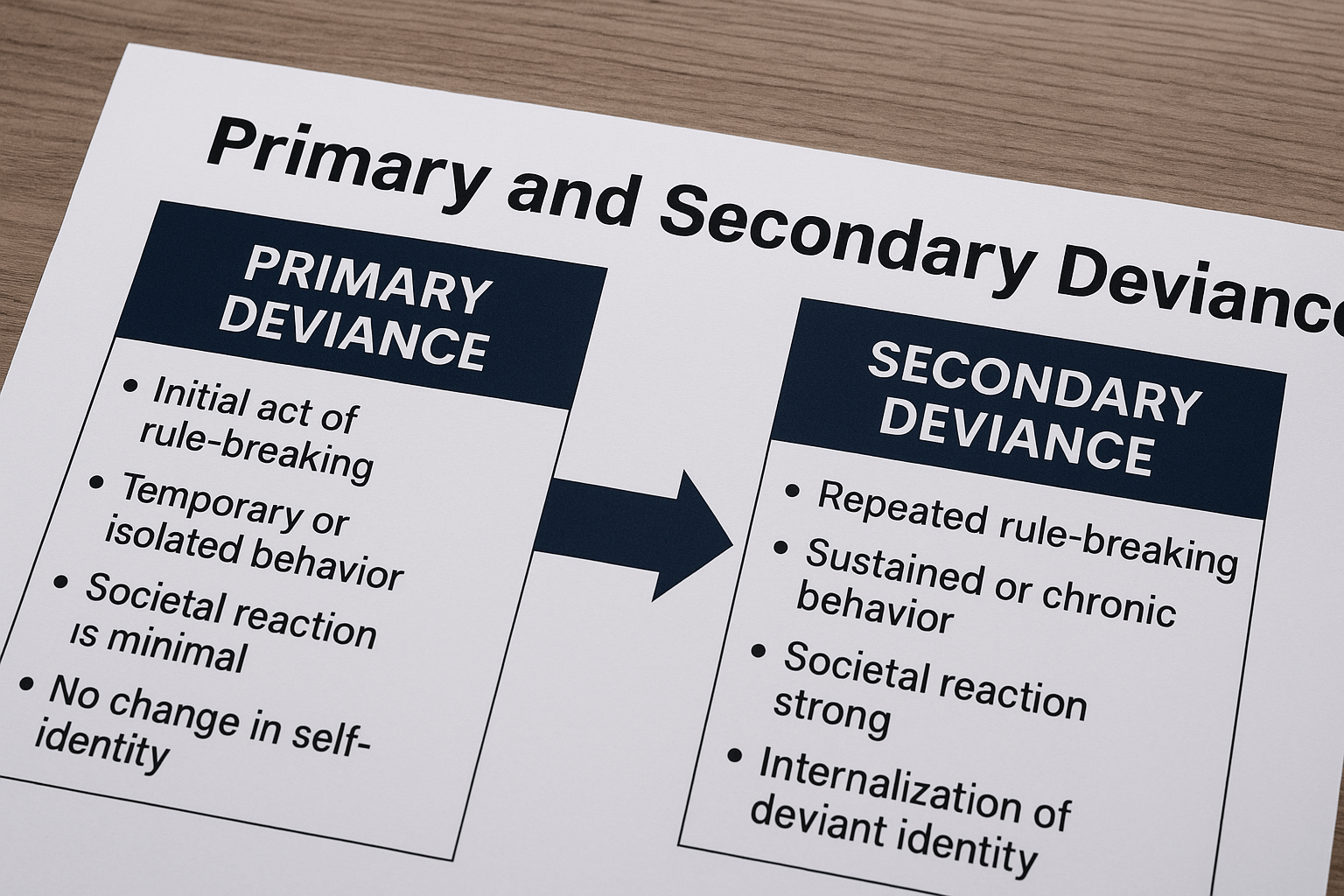

1.2. Primary Deviance

Primary deviance refers to the initial act of rule-breaking. It is typically characterized by being sporadic, context-driven, and not integrated into the individual’s identity. At this stage, the deviant behavior is often rationalized by both the actor and society. It might be seen as a mistake, a phase, or an isolated incident.

Individuals who engage in primary deviance often do so without considering themselves deviant. The behavior might stem from peer influence, stress, or a temporary lapse in judgment. Crucially, at this stage, the person has not yet been socially labeled as deviant in a way that affects their self-concept.

For example:

- A teenager who drinks alcohol at a party to fit in.

- A college student who plagiarizes a paper under academic pressure.

These actions, while against societal or institutional rules, may not lead to long-term consequences unless they are detected and publicly labeled.

1.3. Secondary Deviance

Secondary deviance occurs when an individual is publicly labeled as deviant, and this label begins to influence both how others treat them and how they view themselves. This concept is deeply tied to the theory of symbolic interactionism and emphasizes the role of social labeling in shaping identity.

Once labeled, individuals may begin to internalize the deviant identity, leading to behavioral reinforcement of the deviance. The deviance becomes a central part of their identity rather than an isolated action.

Examples include:

- A juvenile who, after being labeled a delinquent by the school system, begins associating with criminal peers.

- An individual who, after a drug conviction, is rejected from employment opportunities and turns to selling drugs as a means of survival.

Secondary deviance often represents a breakdown in the social control process, where the efforts to punish or stigmatize behavior ironically push individuals further into deviant roles.

2. Theoretical Background

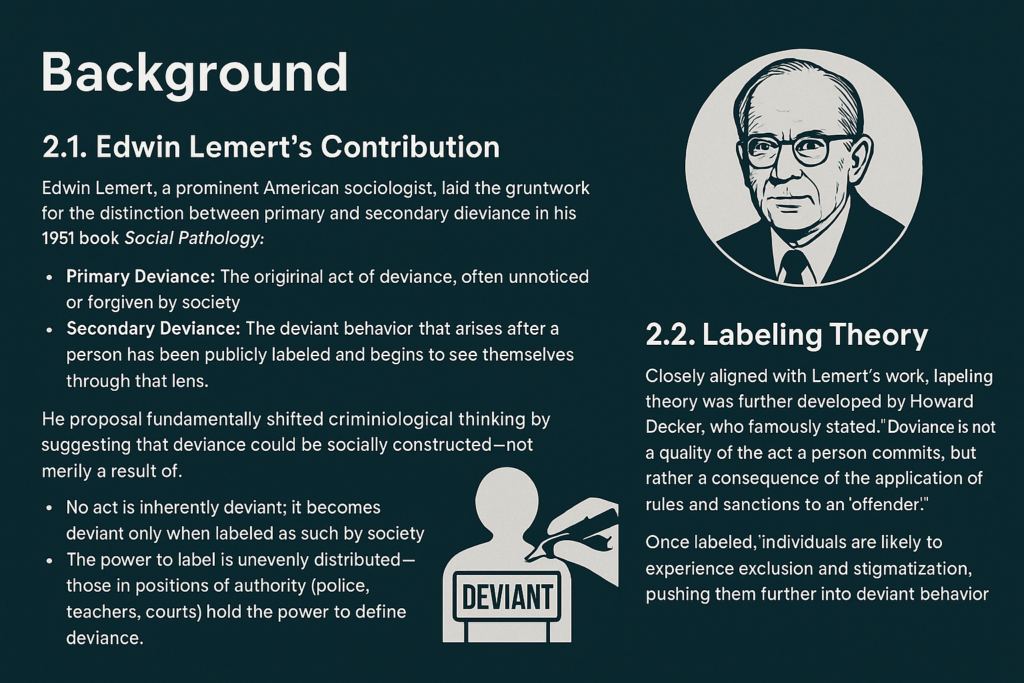

2.1. Edwin Lemert’s Contribution

Edwin Lemert, a prominent American sociologist, laid the groundwork for the distinction between primary and secondary deviance in his 1951 book Social Pathology. Lemert argued that deviance was not simply about rule-breaking behavior but about how society responds to such behavior and how those responses shape future actions.

He proposed a two-phase model:

- Primary Deviance: The original act of deviance, often unnoticed or forgiven by society.

- Secondary Deviance: The deviant behavior that arises after a person has been publicly labeled and begins to see themselves through that lens.

This model fundamentally shifted criminological thinking by suggesting that deviance could be socially constructed—not merely a result of pathology, biology, or poor upbringing.

Lemert‘s theory emphasized the processual nature of deviance, recognizing that individuals move through a trajectory shaped by social reactions, not just personal decisions.

2.2. Labeling Theory

Closely aligned with Lemert’s work, labeling theory was further developed by Howard Becker, who famously stated, “Deviance is not a quality of the act a person commits, but rather a consequence of the application of rules and sanctions to an ‘offender’.”

Labeling theory posits that:

- No act is inherently deviant; it becomes deviant only when labeled as such by society.

- The power to label is unevenly distributed—those in positions of authority (police, teachers, courts) hold the power to define deviance.

- Once labeled, individuals are likely to experience exclusion and stigmatization, pushing them further into deviant behavior.

This theory laid the foundation for analyzing how social power dynamics play a central role in the construction of crime and deviance.

3. Causes and Triggers

3.1. Causes of Primary Deviance

Primary deviance often emerges in contexts where conformity to norms is temporarily suspended, or where socialization processes fail to instill full adherence to rules. Common causes include:

- Peer pressure: Especially prevalent among adolescents who seek group acceptance.

- Economic inequality: Poverty and lack of access to resources often correlate with petty crimes.

- Family issues: Dysfunctional homes can lead to early experimentation with deviance.

- Lack of awareness: Some rule-breaking occurs out of ignorance rather than intent.

- Emotional or psychological stress: Individuals may engage in deviant acts as a coping mechanism.

In most cases, these acts are opportunistic and unplanned rather than a sign of criminal identity.

3.2. Transition to Secondary Deviance

The transition from primary to secondary deviance is not inevitable but mediated by societal reaction. Factors influencing this shift include:

- Severity of punishment or public exposure: Arrests, expulsions, or media coverage.

- Strength of the individual’s support network: Family and community can buffer against labeling.

- Internal psychological resilience: Some individuals resist internalizing deviant labels.

- Availability of alternatives: Educational or vocational pathways can reduce deviant persistence.

3.3. Role of Institutions

Institutions can inadvertently amplify deviance:

Judicial systems often stigmatize first-time offenders with long-lasting records that limit opportunities for reintegration.

Schools label students as “problem children” or “delinquents,” often leading to marginalization.

Police may disproportionately target racial or economic minorities, increasing the likelihood of labeling.

4. Case Studies and Real-Life Applications

4.1. Juvenile Delinquency

Juvenile delinquency is one of the clearest examples of the primary-to-secondary deviance trajectory. Consider a 14-year-old boy who skips school and steals from a convenience store—this may be seen as primary deviance, especially if it’s a first offense. If caught, however, and formally labeled a “juvenile delinquent,” the social response might include suspension, court involvement, or even placement in juvenile detention.

The stigma and institutional response often alienate the individual from conventional pathways such as education or employment. He may internalize the “delinquent” label, seek companionship with other marginalized youth, and develop a stable deviant identity, which is now considered secondary deviance.

4.2. Drug Use and Addiction

Initial experimentation with drugs is typically primary deviance. Many users do not initially consider themselves addicts or deviants. Social response plays a critical role here—if the person is arrested, publicly shamed, or loses employment due to drug use, they may be pushed toward secondary deviance.

After being labeled a “junkie” or “addict,” individuals often find themselves excluded from support systems. This exclusion can lead to increased substance use, dealing drugs, or criminal acts to support the addiction. The behavior now becomes habitual, identity-based, and difficult to reverse.

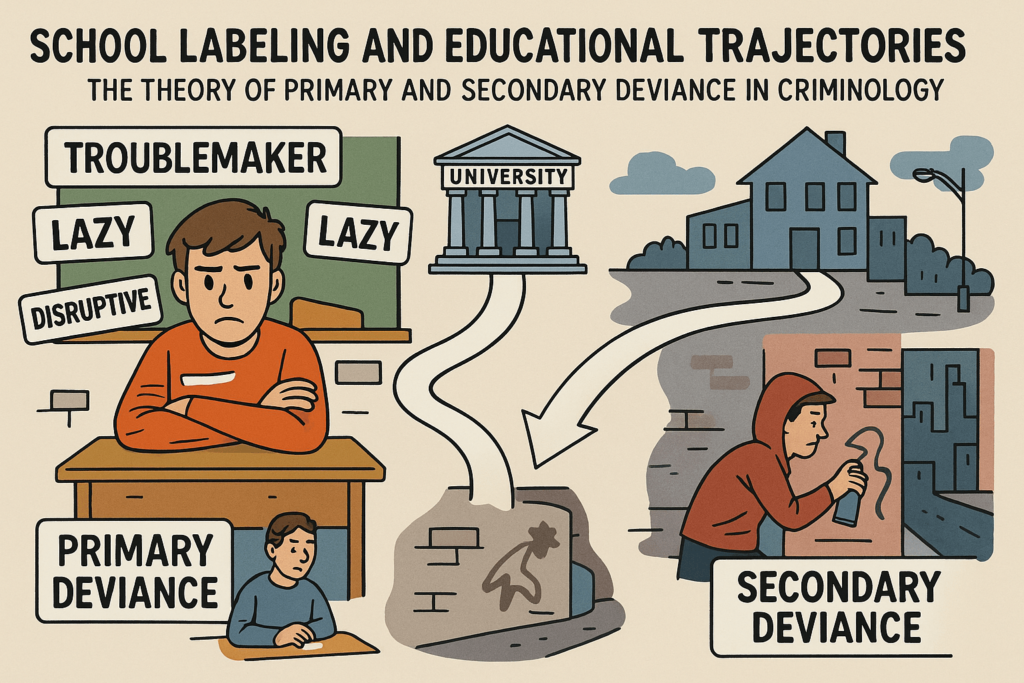

4.3. School Labeling and Educational Trajectories

Studies show that children labeled as “slow,” “troublemakers,” or “unmotivated” from an early age are more likely to disengage from school, perform poorly, and ultimately drop out. This kind of institutional labeling often initiates a process of self-fulfilling prophecy where the student begins to embody the label.

This demonstrates how schools, though tasked with inclusion and development, can become agents of social exclusion when discipline and academic tracking are misapplied or biased.

5. Social Reaction and Identity Formation

5.1. The Power of Social Labels

Labels are not merely descriptors—they carry social weight. A label like “criminal,” “thief,” or “addict” can have devastating consequences on an individual’s self-esteem and identity. Over time, these labels can become internalized, leading the individual to see themselves as unchangeable or irredeemable.

Social identity theory suggests that people seek group belonging. If mainstream society excludes the deviant, they may find belonging in subcultures or deviant peer groups, reinforcing their deviance.

5.2. Stigma and Exclusion

The stigma associated with deviant labels often leads to:

- Loss of employment opportunities

- Reduced social support

- Increased surveillance or control

- Psychological stress or depression

In some cases, stigmatization itself becomes a greater source of harm than the original act of deviance.

5.3. Resistance and Redefinition

Not all individuals internalize deviant labels. Some resist through activism, counter-culture affiliation, or redefinition of their identity. For example:

- LGBTQ+ individuals historically labeled as deviant have redefined their identities through political mobilization.

- Former prisoners may become advocates for criminal justice reform, using their experience to challenge stereotypes.

6. Implications for the Criminal Justice System

6.1. Criminal Labeling and Recidivism

The criminal justice system plays a central role in the process of secondary deviance. When individuals are arrested, tried, and convicted, they often receive a permanent label that affects every aspect of their future life.

Even after serving time, ex-offenders may be:

- Denied housing or employment

- Barred from voting or public services

- Stereotyped in social and professional interactions

This can lead to a cycle of deviance—if legitimate opportunities are closed, returning to criminal behavior may seem like the only viable option.

6.2. Juvenile Justice Reform

Understanding the difference between primary and secondary deviance has led to reform in juvenile justice, including:

- Diversion programs that avoid formal labeling

- Restorative justice initiatives

- Community-based rehabilitation instead of incarceration

Such reforms aim to interrupt the labeling process and reintegrate youth before deviance becomes a core identity.

6.3. Role of Rehabilitation over Punishment

Criminological theories that emphasize labeling support rehabilitation-focused justice systems over punitive ones. Policies informed by this perspective aim to:

- Reduce stigmatization

- Promote reintegration

- Offer mental health and addiction services

- Provide education and vocational training

These approaches address the root causes of deviance rather than reinforcing them through harsh penalties.

7. Criticisms and Limitations of the Theory

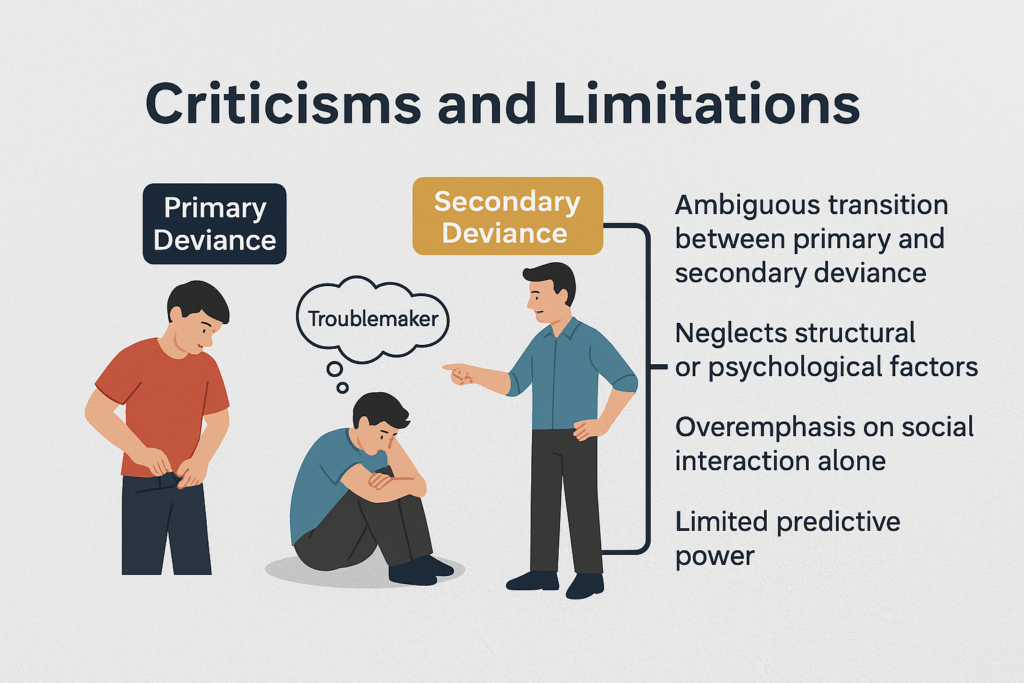

7.1. Overemphasis on Social Reaction

Critics argue that labeling theory overemphasizes social reaction at the expense of individual agency. Not every person labeled as deviant continues down that path, and some may never internalize the label.

7.2. Neglect of Initial Causes

Labeling theory focuses heavily on the process after the act, but says little about what causes primary deviance. Psychological factors, socio-economic status, and family environments are sometimes insufficiently addressed.

7.3. Lack of Predictive Power

The theory is often descriptive rather than predictive. It explains how deviance might evolve but does not always offer testable predictions or variables for empirical study.

7.4. Cultural and Structural Bias

The theory may also overlook broader structural inequalities—such as racism, patriarchy, or capitalism—that influence labeling. For example, why are certain groups more frequently labeled than others? A more intersectional approach is needed.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

The concepts of primary and secondary deviance offer a powerful framework for understanding how behavior transitions from minor rule-breaking to entrenched criminal identity. Lemert’s distinction helps us see deviance not as a static trait, but as a dynamic social process influenced by labels, stigma, and opportunity.

Future criminological research must integrate this theory with:

- Intersectional analysis (race, gender, class)

- Neuroscience and psychology

- Structural criminology

- Restorative justice models

Understanding the trajectory from primary to secondary deviance allows for more humane, effective interventions that focus on restoration and reintegration rather than punishment and exclusion.