Introduction

In the realm of criminology, understanding the social processes that shape and influence criminal behavior is essential for developing effective justice policies. One of the most significant frameworks in this context is Stigma Theory, which explores how societal reactions to deviance—particularly through labeling—can profoundly impact individuals’ identities, behaviors, and life outcomes.

Rooted in the pioneering work of Erving Goffman, stigma theory explains how people who are labeled as “criminals” or “deviants” often internalize these negative labels. This internalization can lead to increased social exclusion, a loss of legitimate opportunities, and a higher likelihood of recidivism. In other words, stigma not only reflects society’s judgment of the individual but can also contribute to the perpetuation of criminal behavior.

This article delves into the role of stigma in the criminal justice system, analyzing how it intersects with labeling theory, affects marginalized populations, and shapes outcomes within society. By examining the criminological implications of stigma, we can better understand the urgent need for reform in how societies respond to crime and deviance.

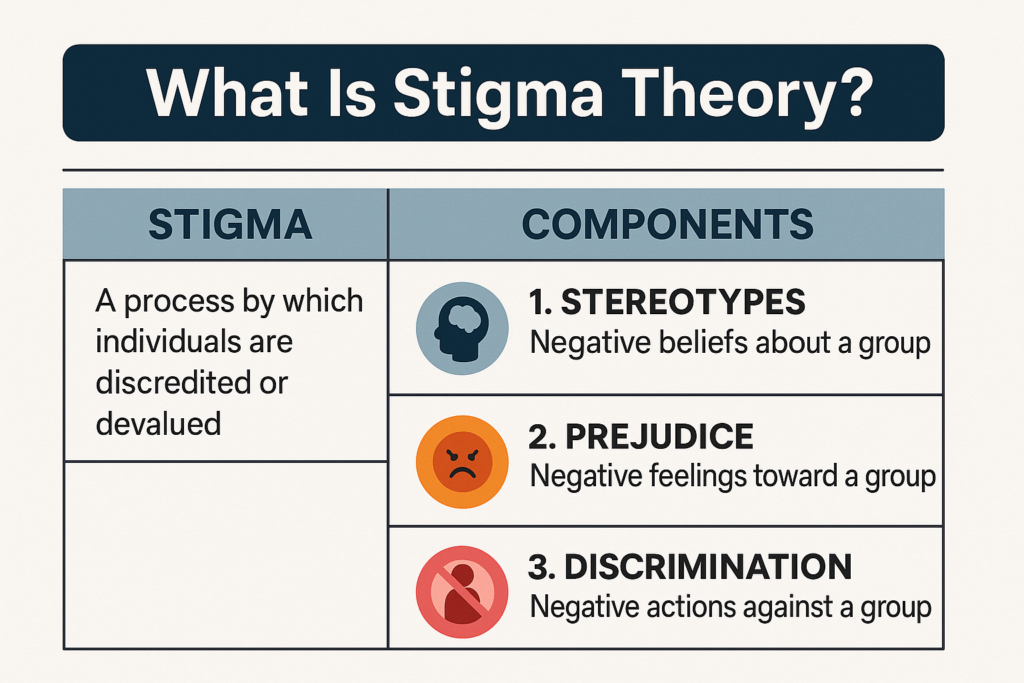

What Is Stigma Theory?

At its core, Stigma Theory examines how societies construct and enforce boundaries between “normal” and “abnormal” people. The term stigma originally referred to a literal mark burned or cut into the skin of ancient Greek slaves and criminals, signifying their degraded status. Goffman revived the concept metaphorically to capture the invisible, symbolic “marks” that modern institutions place upon bodies and biographies through categorization and stereotyping.

Core Definition

Stigma is a powerful social label that identifies an individual or group as fundamentally discredited, discreditable, or tainted in the eyes of others, leading to status loss and discrimination.

What distinguishes stigma from simple difference is the moral judgment embedded in that label. Red hair, for instance, is a difference, but not a stigma in most societies because it carries no moral stigma. HIV, on the other hand, is both a biomedical condition and a stigmatized identity because it is often linked to stereotypes about sexuality, morality, and personal responsibility.

Scope and Reach

Although Stigma Theory originated in sociology, its influence now spans numerous disciplines:

- Public Health uses stigma models to explain why some communities avoid testing, treatment, or vaccination.

- Criminology invokes stigma to understand the life course of formerly incarcerated people.

- Disability Studies critiques how ableist environments produce and perpetuate stigma against people with disabilities.

- Gender and Sexuality Studies apply stigma frameworks to unpack homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny.

- Economics has begun modeling the cost of stigma‑related exclusion on labor markets and national productivity.

The universality of stigma’s basic mechanisms means that Stigma Theory is as relevant to global South contexts as it is to the global North, and as applicable to digital spaces as it is to physical neighborhoods.

The Origins of Stigma Theory

Erving Goffman’s Foundational Contribution

Erving Goffman, a towering figure in symbolic interactionism, first articulated a systematic theory of stigma in the early 1960s. Working against the backdrop of civil‑rights struggles, de‑institutionalization of psychiatric hospitals, and emerging disability rights movements, Goffman argued that stigma arises from social interactions rather than intrinsic defects.

He proposed three broad categories of stigma:

- Physical Stigmas – visible bodily differences such as paralysis, disfigurement, or missing limbs.

- Character Stigmas – perceived moral failings such as addiction, unemployment, or criminal conviction.

- Tribal Stigmas – collective attributes like race, nationality, religion, or class that can result in inherited stigma.

Goffman’s work emphasized how stigmatized individuals engage in information management—concealing, disclosing, or strategically highlighting aspects of their identity to minimize social sanctions. His insight that stigma simultaneously lives “in the situation” (the social encounter) and “in the person” (the internalized identity) fundamentally transformed the study of difference.

Intellectual Precursors and Expansions

Although Goffman popularized Stigma Theory, earlier thinkers laid groundwork. Émile Durkheim wrote about how societies define deviance to reinforce collective consciousness. W. E. B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” anticipated the internal conflict stigmatized individuals experience. Post‑Goffman, scholars such as Link and Phelan integrated structural power and institutional discrimination into Stigma Theory, arguing that stigma is inextricably tied to social, economic, and political power.

Today, Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw) and Identity Process Theory (Breakwell) further refine Stigma Theory by showing how overlapping stigmas (e.g., race and gender) interact, and how identity is negotiated under threat.

Key Concepts in Stigma Theory

1. Social Labeling

Labeling is the process by which society assigns categories—and implicit judgments—to people. Howard Becker’s Labeling Theory dovetails with Stigma Theory in arguing that deviance is not inherent in an act but is ascribed by audiences. Labels like “criminal,” “illegal immigrant,” or “welfare queen” shape public policy and personal outcomes long after the material facts of a case have faded.

2. Spoiled Identity

A spoiled identity is Goffman’s term for the self that has been tainted by stigma. Internalizing a spoiled identity can produce self‑stigma, where individuals begin to believe negative stereotypes about themselves, leading to diminished self‑esteem, social withdrawal, and mental‑health challenges.

3. Discredited vs. Discreditable Stigmas

- Discredited stigmas are visible or widely known (e.g., wheelchair use, facial scars). The management problem here is how to deal with existing reactions.

- Discreditable stigmas are invisible or concealable (e.g., certain mental illnesses, HIV status). The management problem is deciding whether, when, and how to disclose.

4. Courtesy Stigma (Associative Stigma)

Family members, friends, or professionals associated with a stigmatized individual can experience courtesy stigma. For example, parents of autistic children often face blame for their child’s behavior, while doctors treating COVID‑19 patients experienced stigma early in the pandemic.

5. Structural Stigma

While early work on stigma focused on micro‑interactions, current scholars emphasize structural stigma—institutional policies, cultural ideologies, and systemic barriers that disadvantage certain groups. Anti‑homosexuality laws, segregated schooling, and insurance exclusions for pre‑existing conditions are all examples of structural stigma.

6. Stigma Power

Link, Phelan, and Hatzenbuehler describe stigma power as the capacity to keep people “down, in, or away.” Dominant groups deploy stigma to justify inequality, control resources, and reinforce social hierarchies.

Real‑Life Applications of Stigma Theory

The theoretical elegance of Stigma Theory finds its most compelling justification in real‑world applications. The following domains illustrate how research grounded in stigma has informed practice, policy, and activism.

Mental Health Stigma

Globally, mental illness is among the most stigmatized conditions. The World Health Organization estimates that depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, yet fewer than half of those affected receive treatment. Studies rooted in Stigma Theory reveal that fear of labeling, social rejection, or job loss often prevents individuals from seeking help.

- Case Example: In Japan, the term seishin‑byō (literally “mind disease”) carried such heavy stigma that the government replaced it with kōritsushōgai (“affective disorder”) in 2002, leading to higher treatment rates for schizophrenia.

HIV/AIDS Stigma

HIV‑related stigma was so severe in the 1980s that it was dubbed the “second epidemic.” Even today, UNAIDS reports that 15 % of people living with HIV in high‑prevalence countries avoid clinics for fear of gossip. Scholars applying Stigma Theory have pushed for rights‑based interventions, confidential testing, and community‑led counseling to reduce stigma.

- Policy Impact: South Africa’s 2003 Operational Plan for comprehensive HIV and AIDS care explicitly cited stigma as a barrier, leading to nationwide anti‑stigma media campaigns.

Disability Stigma

The social model of disability, which frames disability as a product of inaccessible environments rather than individual impairments, owes an intellectual debt to Stigma Theory. Ramps, captions, and inclusive curricula are not just accommodations; they are anti‑stigma tools that relocate the “problem” from the body to society.

Criminal Record Stigma

Formerly incarcerated individuals face significant barriers to employment, housing, and civic participation. Sociologists document how a single label—”ex‑offender”—can eclipse all other aspects of identity. Ban‑the‑Box campaigns, which remove criminal‑record checkboxes from job applications, stem directly from stigma research.

Poverty and Welfare Stigma

Public discourse often blames poor people for their situation, framing poverty as a personal failing rather than a structural issue. Stigma Theory helps explain how such narratives justify punitive policies like drug testing welfare recipients, despite no evidence that recipients use drugs at higher rates than non‑recipients.

Intersectional Stigma

Stigma rarely occurs in isolation. A Black transgender woman living with HIV navigates racial, gender, sexual‑orientation, and health‑related stigmas simultaneously. Intersectionality frameworks merged with Stigma Theory show that overlapping stigmas interact multiplicatively, not additively.

The Social Impact of Stigma

Stigma has cascading consequences at multiple levels.

Individual Level

- Psychological Distress: Chronic exposure to stigma correlates with anxiety, depression, and suicidality.

- Behavioral Coping: Individuals may avoid healthcare, decline promotions, or change schools to escape stigmatizing contexts.

- Economic Penalty: A tagged identity can limit job prospects, leading to lifetime earnings gaps that mirror those caused by formal discrimination.

Interpersonal Level

- Family Stress: Courtesy stigma can strain family relationships and caregiving resources.

- Peer Dynamics: Bullying and social exclusion in schools or workplaces reproduce stigma across generations.

Community Level

- Public Health Risks: When marginalized groups avoid clinics or vaccination sites, herd immunity thresholds falter.

- Knowledge Gaps: Stigmatized topics become taboo, hindering education and public discourse.

Societal Level

- Policy Formation: Stigmatizing rhetoric shapes laws that criminalize poverty, substance use, or migration.

- Economic Cost: The World Bank estimates that disability stigma alone costs economies up to 7 % of GDP through lost productivity and extra healthcare expenses.

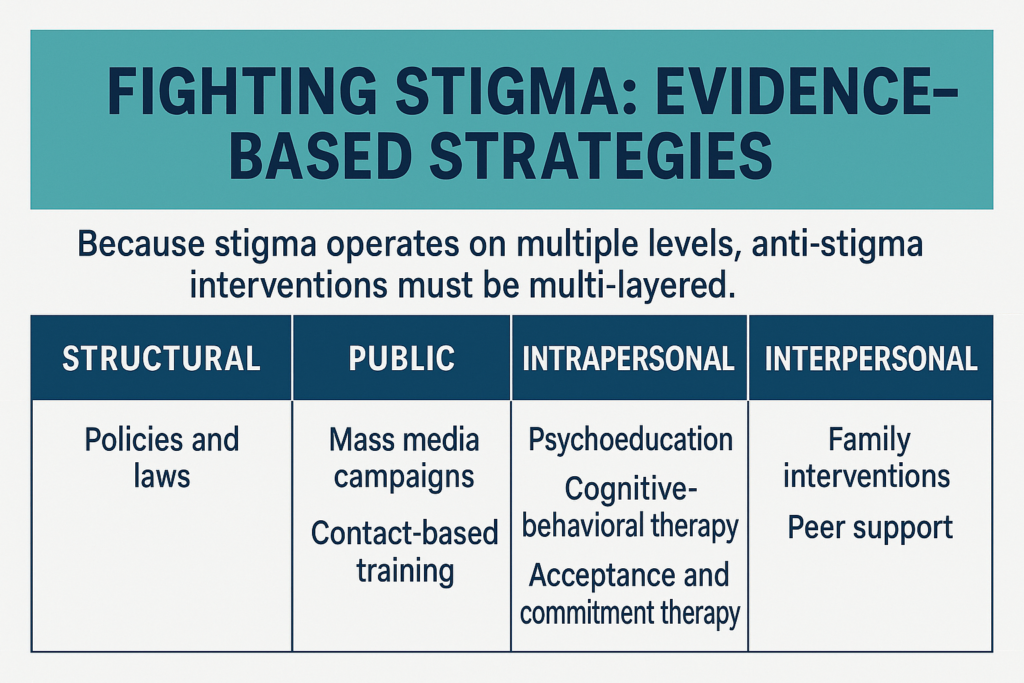

Fighting Stigma: Evidence‑Based Strategies

Because stigma operates on multiple levels, anti‑stigma interventions must be multi‑layered.

1. Education and Awareness

School‑based curricula that include lived‑experience testimonies reduce stigma more effectively than lecture‑only models. Contact‑based education—meeting people from stigmatized groups—outperforms mere information campaigns.

2. Media Representation

Positive portrayals of stigmatized individuals in film, television, and social media challenge stereotypes. The success of shows like Queer Eye and Special (about a gay man with cerebral palsy) illustrates media’s power to normalize difference.

3. Legal and Policy Reform

Anti‑discrimination legislation shifts social norms by signaling societal condemnation of prejudice. Laws matter not only for enforcement but also for symbolically affirming equal citizenship.

4. Empowerment and Peer Support

Self‑help groups, peer navigators, and user‑led advocacy place stigmatized people at the center of change, fostering resilience and collective identity.

5. Technology and Digital Spaces

Mobile apps that anonymize mental‑health counseling, or blockchain systems protecting medical data, reduce exposure to stigma. Yet digital spaces can also amplify stigma through cyberbullying, making digital literacy crucial.

The Significance of Stigma Theory in Modern Scholarship

Over the past two decades, academic interest in stigma has exploded.

- Citation Growth: A Google Scholar search for “stigma” yields over four million results as of 2025, with annual citations increasing ten‑fold since 2000.

- Interdisciplinary Reach: Fields as diverse as veterinary medicine (stigma of veterinarians seeking mental‑health care) and computer science (algorithmic bias as digital stigma) now engage with Stigma Theory.

- Methodological Innovations: Researchers deploy mixed‑methods designs—combining ethnography, big‑data analytics, and neuroimaging—to capture stigma’s complexity.

- Global South Perspectives: Scholars from India, Nigeria, and Brazil critique Western bias in stigma research, calling for decolonized frameworks that address local realities such as caste stigma or albinism stigma.

Stigma Theory thus continues to evolve, offering robust tools for analyzing the shifting terrain of identity politics, health disparities, and social justice.

Stigma Theory in Criminology

Stigma Theory in criminology explores how individuals are socially labeled and how these labels affect their identity, behavior, and treatment within the criminal justice system. Originally derived from Erving Goffman’s foundational work, stigma refers to a deeply discrediting attribute that reduces someone “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one.” Within criminology, this theory has significant implications for understanding criminal behavior, social reactions, and long-term consequences for offenders.

Stigmatization begins the moment an individual is associated with a criminal act. Even before formal prosecution, mere suspicion or accusation can lead to social labeling. Society often categorizes individuals as “deviants,” “criminals,” or “offenders,” creating an identity that may persist regardless of future behavior. This label becomes a form of social control and can limit the opportunities available to individuals, such as employment, housing, and education, which can, in turn, increase the likelihood of recidivism.

One of the most important contributions of Stigma Theory in criminology is its connection to Labeling Theory. According to this framework, labeling someone as a criminal reinforces deviant behavior because it shapes self-perception and social interactions. Individuals internalize the stigmatizing label and begin to act in ways consistent with that identity, which leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy. Instead of rehabilitation, the criminal justice system often reinforces negative labels, contributing to a cycle of deviance.

Criminologists also study how institutional stigma impacts marginalized groups. For example, minority communities often face disproportionate levels of policing, incarceration, and surveillance, leading to collective stigma. This systemic bias not only affects individuals but also entire communities, perpetuating mistrust in the legal system and creating structural barriers to reintegration. Stigma in criminology thus reflects broader issues of social inequality, discrimination, and power dynamics.

Programs such as restorative justice, community-based rehabilitation, and expungement of criminal records are modern responses that attempt to reduce the effects of stigma. These interventions focus on reintegration rather than punishment and aim to shift public perception of former offenders. By addressing the root causes of stigma and promoting inclusive policies, criminologists hope to reduce the social consequences of criminal labeling.

In summary, Stigma Theory in criminology highlights the profound effects of societal labeling on individuals involved with the criminal justice system. It calls for a more humane, equitable approach that considers the long-term social impact of criminal records and public perceptions. Understanding stigma is essential for designing policies that encourage rehabilitation, reduce recidivism, and promote social justice.

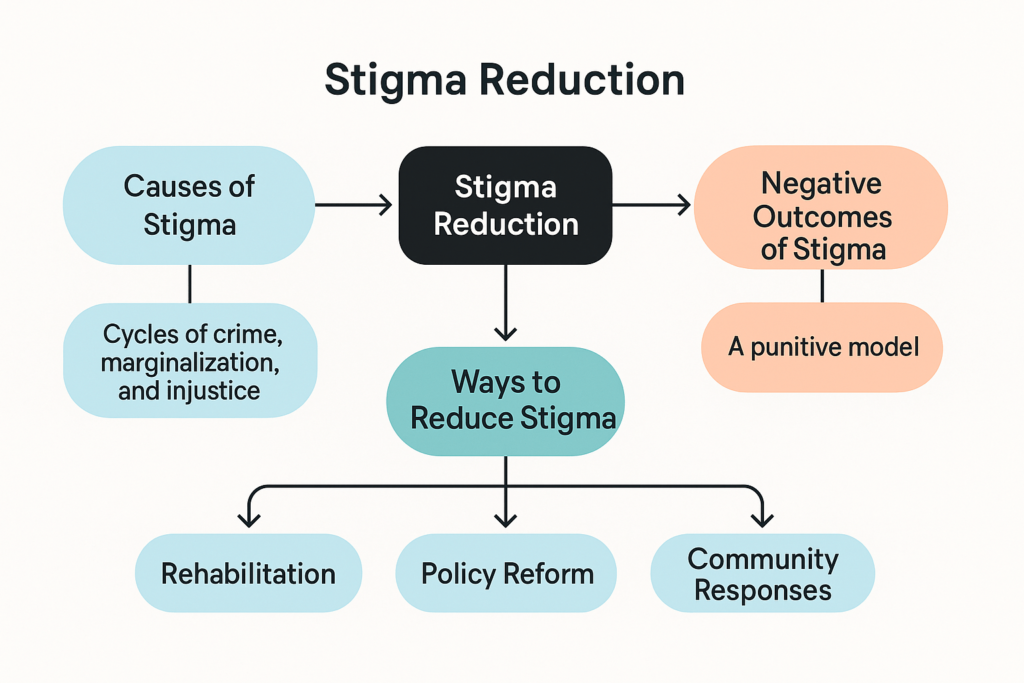

Stigma Reduction: Rehabilitation, Policy Reform, and Community Responses

Reducing stigma in the realm of criminology is not only possible—it is essential. Stigma reinforces cycles of crime, marginalization, and injustice. By addressing it directly through social policy, institutional reform, rehabilitation programs, and public awareness, we can shift from a punitive model to a restorative and inclusive approach.

1. Rehabilitation and Restorative Justice

Traditional punishment often reinforces stigma. In contrast, rehabilitation and restorative justice seek to:

- Heal the harm caused by crime rather than simply punish the offender.

- Involve victims, offenders, and communities in dialogue and accountability.

- Focus on identity transformation, empathy development, and reintegration.

Programs based on these principles, such as Norway’s prison system or New Zealand’s restorative courts, have achieved:

- Lower recidivism rates.

- Reduced societal stigma.

- Higher satisfaction among victims and communities.

2. “Ban the Box” and Employment Policy Reform

One of the most direct ways to fight stigma is to remove structural barriers to reentry:

- The “Ban the Box” campaign advocates for removing the checkbox about criminal records from job applications.

- Many states and countries have already adopted this policy, leading to:

- Increased hiring of formerly incarcerated people.

- Decreased reliance on background checks as a blanket disqualifier.

Additionally, incentive programs for employers, such as tax credits or liability protections, can further encourage hiring without bias.

3. Media Representation and Public Education

Mass media plays a central role in shaping public attitudes about crime and criminals. To reduce stigma:

- News outlets should avoid sensationalist or dehumanizing language (e.g., “monster,” “thug”).

- Documentaries, films, and campaigns should highlight stories of rehabilitation and systemic injustice.

- Public education campaigns can reframe crime not as a personal defect but as a social issue rooted in poverty, trauma, and inequality.

Examples include:

- The Marshall Project’s storytelling initiatives.

- Former inmates using platforms like TED Talks or podcasts to tell their own stories.

- Social media movements such as #SecondChances and #Cut50.

4. Legislative and Criminal Justice Reform

Systemic stigma requires systemic change:

- Decriminalizing nonviolent offenses (e.g., drug possession, sex work) can reduce unnecessary labeling.

- Ending mandatory minimum sentences allows for more individualized and rehabilitative justice.

- Expanding record sealing and expungement laws gives people a genuine second chance.

These reforms shift the focus from punishment to opportunity and dignity.

5. Community Support and Peer Advocacy

Community-based initiatives are among the most effective tools for reducing stigma:

- Reentry programs that offer housing, job training, mental health services, and peer mentoring are vital.

- Formerly incarcerated individuals can become advocates and mentors, offering credibility and empathy.

- Faith communities, non-profits, and neighborhood groups can promote acceptance and reintegration.

Examples:

- The Fortune Society (New York).

- Homeboy Industries (Los Angeles).

- Community circles and peacemaking programs in Indigenous communities.

6. Education and Prevention in Schools

Preventing stigma starts early:

- School-based programs can teach empathy, conflict resolution, and restorative practices.

- Anti-bullying campaigns and trauma-informed education help reduce labeling in youth settings.

- Diverting at-risk youth from the justice system prevents the early application of criminal stigma.

Conclusion

Stigma Theory teaches us that prejudice is not a natural reaction to difference but a learned response embedded in social structures and maintained by power. By labeling certain bodies, behaviors, or backgrounds as inherently flawed, societies allocate resources, opportunities, and dignity in unequal ways. The human toll is measurable in lost lives, wasted talent, and persistent inequity.

Yet the same social processes that create stigma can dismantle it. Laws can change, media narratives can shift, communities can organize, and individuals can resist internalized shame. Armed with the insights of Stigma Theory, activists and policymakers have already reduced stigma around HIV, disability, and mental health in many regions. The task now is to extend those gains to every sphere where stigma persists—from prisons to parliaments, from playgrounds to digital platforms.