Introduction: A Social Lens on Crime

Criminology, the scientific study of crime and criminal behavior, has long drawn upon various theoretical frameworks to explain why individuals deviate from social norms. Among these, Symbolic Interactionism offers a unique and deeply sociological perspective. Rather than viewing crime purely through biological or structural lenses, Symbolic Interactionism emphasizes the meanings and symbols individuals assign to their social world.

This perspective shifts the focus from macro-level structures to micro-level interactions, asking: How do individuals come to see themselves as criminals? How do social labels and reactions shape future behavior? By understanding crime through the prism of social symbols, we begin to see that criminality is not merely an act, but a process constructed through interaction.

Historical Origins and Key Thinkers

Symbolic Interactionism emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the rigid determinism of earlier sociological theories. Its intellectual foundations are deeply rooted in American pragmatism, particularly in the works of George Herbert Mead, who emphasized the role of communication and social interaction in the development of self and society.

George Herbert Mead

Mead’s theory of the “self” as a social product was pivotal. According to him, individuals develop self-concepts through the process of social interaction—especially through role-taking and the internalization of others’ perspectives. Though Mead did not publish extensively, his ideas were systematized by his student Herbert Blumer, who coined the term Symbolic Interactionism and laid out its three core principles:

- Humans act based on the meanings things have for them.

- These meanings arise from social interaction.

- Meanings are modified through an interpretive process.

Blumer’s influence shaped generations of sociologists and criminologists, including Howard Becker and Erving Goffman, whose contributions further integrated Symbolic Interactionism into criminological discourse.

Core Concepts of Symbolic Interactionism

To fully grasp its application in criminology, it’s essential to understand Symbolic Interactionism’s core ideas:

- Symbols and Meaning: Social life is organized around symbols (e.g., language, gestures, clothing), and individuals behave based on the meanings they assign to these symbols.

- The Self and Identity: The self is not static but continually formed through interaction. The concept of the looking-glass self, proposed by Charles Horton Cooley, illustrates how individuals see themselves based on how they believe others perceive them.

- Role-Taking and Social Interaction: Individuals adopt roles and act out behaviors based on social expectations, constantly adjusting to the reactions of others.

In criminology, these concepts help explain how individuals come to define themselves as “deviant” or “criminal”—often as a result of being labeled or stigmatized by society.

Crime as a Socially Constructed Phenomenon

Traditional criminological theories such as biological positivism or rational choice theory often treat crime as an objective behavior that can be measured and punished accordingly. In contrast, Symbolic Interactionism views crime as a social construct—an outcome of the meanings people attribute to behaviors and how society responds to them.

For instance, the same act (like graffiti or trespassing) may be labeled as criminal in one context and artistic or rebellious in another. The social audience, not the act itself, often determines what is deemed criminal.

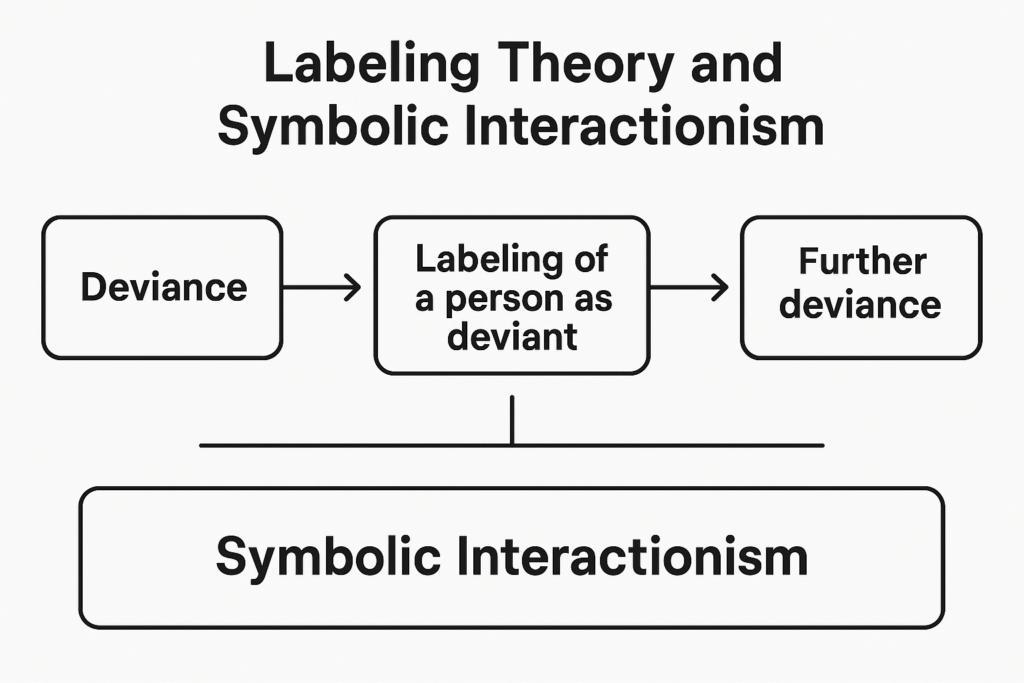

Labeling Theory and Symbolic Interactionism

Labeling Theory, perhaps the most prominent criminological application of Symbolic Interactionism, was pioneered by Howard S. Becker in his seminal work Outsiders (1963). Becker famously stated: “Deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules and sanctions.”

Primary and Secondary Deviance

Building on Labeling Theory, Edwin Lemert introduced the concepts of:

- Primary Deviance: The initial act of rule-breaking, which may go unnoticed or be lightly sanctioned.

- Secondary Deviance: The process by which a person begins to identify as deviant due to societal reactions and labeling, often leading to continued deviance.

This progression illustrates the core insight of Symbolic Interactionism: deviance—and therefore crime—is not just about what one does, but about how one is perceived and treated by others.

Stigma and the Criminal Identity

The work of Erving Goffman further illuminates the power of social interaction in shaping criminal behavior. In Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1963), Goffman explored how individuals labeled as deviant carry a “spoiled identity” that affects all future interactions.

A person who has served prison time may face social exclusion, employment discrimination, and strained relationships. These responses can reinforce the individual’s deviant identity, making reintegration into society difficult and increasing the likelihood of recidivism.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

The theoretical power of Symbolic Interactionism comes to life in its real-world applications. Several studies and sociological observations have demonstrated how labeling, interaction, and social symbolism contribute to the construction of criminal identities.

The School-to-Prison Pipeline

In educational settings, symbolic interactionists have explored how disciplinary practices contribute to criminal labeling early in life. When teachers and administrators label certain students—often from marginalized backgrounds—as “troublemakers,” these students internalize the label and begin to perform accordingly. Studies show that zero-tolerance policies and school surveillance often disproportionately affect Black and Latino youth, reinforcing stereotypes and facilitating contact with the criminal justice system.

Policing and Public Perception

Street-level policing practices often rely on symbols—clothing styles, location, body language—to determine suspicion. For example, broken windows policing, rooted in symbolic interpretations of urban disorder, disproportionately targets minor infractions. Symbolic Interactionism helps explain how these patterns create feedback loops between perceived disorder and over-policing, leading to cumulative disadvantage and criminal labeling in entire communities.

Reintegration and Desistance

Programs that help former offenders reintegrate into society often succeed by reshaping the symbolic and interactional environment. Initiatives that emphasize restorative justice or community reintegration help individuals shed deviant identities and adopt new ones—such as “community member,” “father,” or “employee”—through supportive, symbolic interactions.

Comparison with Other Criminological Theories

While Symbolic Interactionism offers deep insight into the micro-level processes of deviance and crime, it differs significantly from other criminological theories that operate at structural or individual levels.

Differential Association Theory (Edwin Sutherland)

Though closely related, Differential Association Theory posits that criminal behavior is learned through interaction with others. While both theories emphasize social interaction, Symbolic Interactionism focuses more on meaning and identity, whereas Sutherland emphasizes behavior transmission.

Strain Theory (Robert Merton)

Merton’s Strain Theory suggests that crime results from a disjunction between societal goals and the means available to achieve them. Unlike Symbolic Interactionism, which zooms in on symbolic interpretation, Strain Theory offers a more structural explanation of deviance.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists, such as Richard Quinney, argue that laws and criminal labels are tools used by the ruling class to control the marginalized. While Symbolic Interactionism explores how criminal identities are formed, Conflict Theory asks why certain groups are labeled criminal in the first place—focusing more on power and inequality.

By integrating insights from these diverse frameworks, Symbolic Interactionism becomes even more powerful. It doesn’t replace structural explanations, but complements them by showing how macro forces play out in everyday interactions.

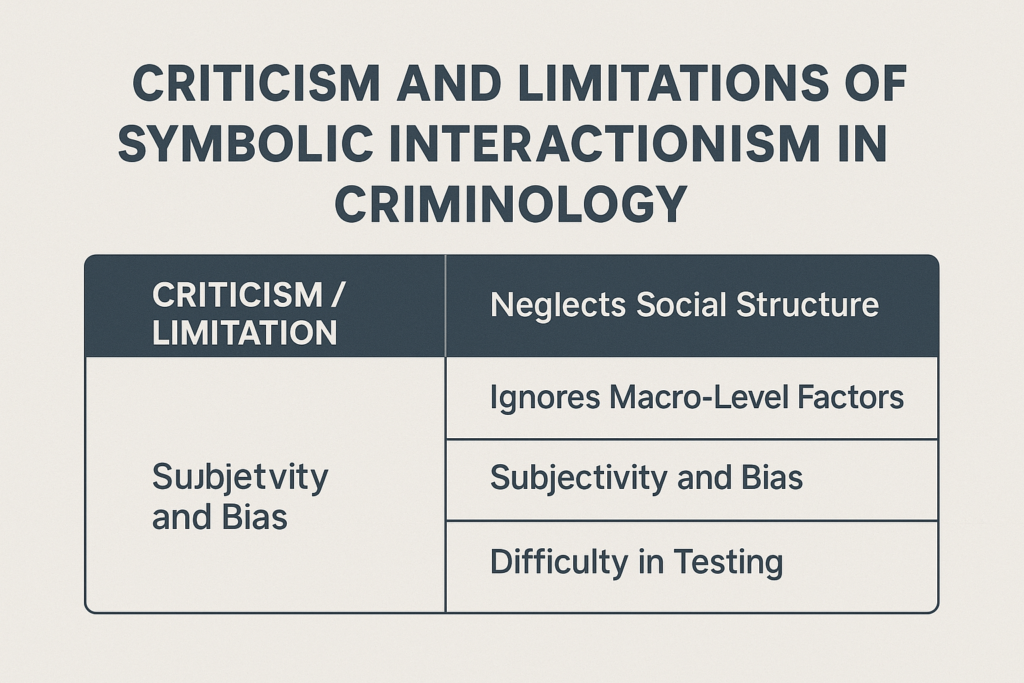

Criticism and Limitations of Symbolic Interactionism in Criminology

Despite its strengths, Symbolic Interactionism is not without critique. Scholars have raised several important limitations:

Neglect of Structural Factors

Critics argue that Symbolic Interactionism can underemphasize structural forces such as poverty, institutional racism, and systemic inequality. While it adeptly explains how deviance is constructed, it often lacks tools to explain why certain groups are more vulnerable to criminal labeling in the first place.

Lack of Predictive Power

Unlike theories grounded in data and cause-effect relationships, Symbolic Interactionism is qualitative and interpretive. This makes it rich in depth but weak in prediction, leading some to dismiss it as less “scientific.”

Fragmentation and Vagueness

Because Symbolic Interactionism encompasses a broad range of symbolic interactions, some critics see it as too fragmented. Without a unified model or strict definitions, its applicability can sometimes seem too loose or subjective.

Symbolic Interactionism and Its Relationship with Other Criminological Theories

Symbolic Interactionism offers a micro-level lens on deviance and crime, emphasizing the meanings individuals attach to behaviors and how societal reactions shape identity. However, it exists within a broader theoretical landscape in criminology, where other frameworks address crime from structural, psychological, biological, and rational perspectives. Understanding Symbolic Interactionism’s relationship with these theories allows for a more holistic view of criminal behavior.

1. Symbolic Interactionism vs. Strain Theory

Strain Theory, formulated by Robert K. Merton, argues that deviance arises when individuals experience a disconnect between culturally approved goals (like wealth) and the institutional means to achieve them (like employment). In contrast, Symbolic Interactionism does not emphasize structural strain or economic pressure but focuses on how individuals come to see themselves—and are seen by others—as deviant.

While Strain Theory explains the why of deviant behavior at a societal level, Symbolic Interactionism explains how deviance is constructed and reinforced through interaction. For example, someone who resorts to theft due to blocked opportunities (strain) might later embrace a deviant identity if they are labeled a “thief” by society—an identity formed through symbolic interaction.

Thus, both theories can work complementarily: Strain Theory explains the initial cause of deviance, and Symbolic Interactionism explores how deviant identities are formed and sustained.

2. Interactionism and Social Learning/Differential Association Theory

Edwin Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory suggests that criminal behavior is learned through association with others who commit crimes. This learning includes techniques, motives, and rationalizations for deviant behavior. Like Symbolic Interactionism, it highlights social interaction as central to understanding crime.

The two theories overlap significantly:

- Both emphasize social context and peer influence.

- Both reject biological determinism.

- Both treat crime as a learned behavior.

However, Symbolic Interactionism delves more deeply into the construction of meaning and identity. Where Sutherland focuses on behavior transmission, Symbolic Interactionism asks: How do individuals internalize deviant roles? and How do social reactions shape identity?

For instance, a young person might learn criminal behavior in a peer group (Differential Association) but only begins to see themselves as a “criminal” after being caught, labeled, and ostracized (Symbolic Interactionism).

3. Symbolic Interactionism and Control Theories

Control theories, such as Hirschi’s Social Bond Theory, assert that people commit crimes when their bonds to society (attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief) weaken. These theories assume that deviance is natural unless restrained by strong social ties.

Symbolic Interactionism offers a different perspective: deviance is not inherent but is socially created through interactions and symbolic interpretations. While Control Theory explains crime in terms of absence of conformity, Symbolic Interactionism explains how definitions of deviance are negotiated through social discourse.

Moreover, Control Theories tend to focus on external constraints, whereas Symbolic Interactionism examines internal identity processes. One sees crime as a failure of socialization; the other sees it as a dynamic outcome of social labeling and interaction.

4. Interactionism and Conflict Theory

Conflict Theory, rooted in the work of Karl Marx and extended by criminologists like Richard Quinney, views crime through the lens of social inequality. It argues that laws are tools used by the ruling class to oppress the marginalized. From this perspective, criminal labels are applied selectively to maintain class, racial, and gender hierarchies.

There is synergy between Symbolic Interactionism and Conflict Theory:

- Both critique the objectivity of criminal law.

- Both argue that deviance is socially constructed.

- Both recognize the power dynamics in labeling.

However, the emphasis differs. Conflict Theory operates at a macro level, analyzing systems of power and oppression. Symbolic Interactionism works at the micro level, exploring how individuals internalize these labels and perform deviance. Together, they reveal a full picture: Conflict Theory shows who gets labeled, and Symbolic Interactionism shows what happens after the label is applied.

5. Interactionism and Rational Choice/Classical Criminology

Rational Choice Theory and classical perspectives view individuals as rational actors who weigh the costs and benefits of committing a crime. These theories focus on decision-making processes and deterrence.

Symbolic Interactionism contrasts sharply here:

- It does not assume rationality.

- It emphasizes social meaning, not calculation.

- It sees crime as a product of interaction, not an isolated choice.

Nevertheless, the theories can be used together in layered analysis. For example, while Rational Choice might explain why a person chooses a specific criminal act, Symbolic Interactionism can explain how that person came to see crime as an acceptable part of their identity.

6. Integration: Toward a Holistic Criminology

Modern criminologists increasingly advocate for theoretical integration, combining the insights of multiple theories to better explain the complexity of criminal behavior. Symbolic Interactionism’s attention to identity, meaning, and symbolic power makes it a valuable complement to more deterministic or structural theories.

It helps answer questions like:

- Why do some individuals reoffend after punishment while others desist?

- How does being labeled a “felon” affect life choices and self-perception?

- Why does the same act carry different meanings in different cultural or social contexts?

By integrating Symbolic Interactionism with other perspectives, we gain a multidimensional understanding of crime—as an outcome of choice, environment, inequality, and social interaction.

Conclusion: A Dialogue, Not a Competition

Rather than viewing criminological theories in opposition, it is more productive to see them as part of a dialogue. Symbolic Interactionism fills crucial gaps left by macro theories, providing insight into the human experience of crime. It reminds us that behind every statistic is a story—shaped by symbols, interactions, and the search for meaning.

Conclusion: The Continuing Relevance of Symbolic Interactionism

In an era of mass incarceration, social media surveillance, and identity politics, Symbolic Interactionism remains a profoundly relevant lens for understanding crime. It teaches us that criminality is not just about actions, but about meanings, perceptions, and interactions.

By exploring how identities are formed and transformed in the social arena, Symbolic Interactionism reminds us that no individual is born a criminal. Rather, criminality is a negotiated identity, influenced by social labels, symbolic environments, and interpersonal reactions.

Implications for Policy and Practice

- Rehabilitation over punishment: Policies should aim to prevent the internalization of deviant identities.

- Restorative justice: Repairing relationships and redefining identities can reduce recidivism.

- Anti-labeling practices: Schools, police, and courts should adopt interactional practices that avoid stigmatization.

Criminology students, researchers, and practitioners alike can benefit from revisiting Symbolic Interactionism—not as a replacement for structural theories, but as a complementary framework that adds nuance, empathy, and human depth to our understanding of crime.