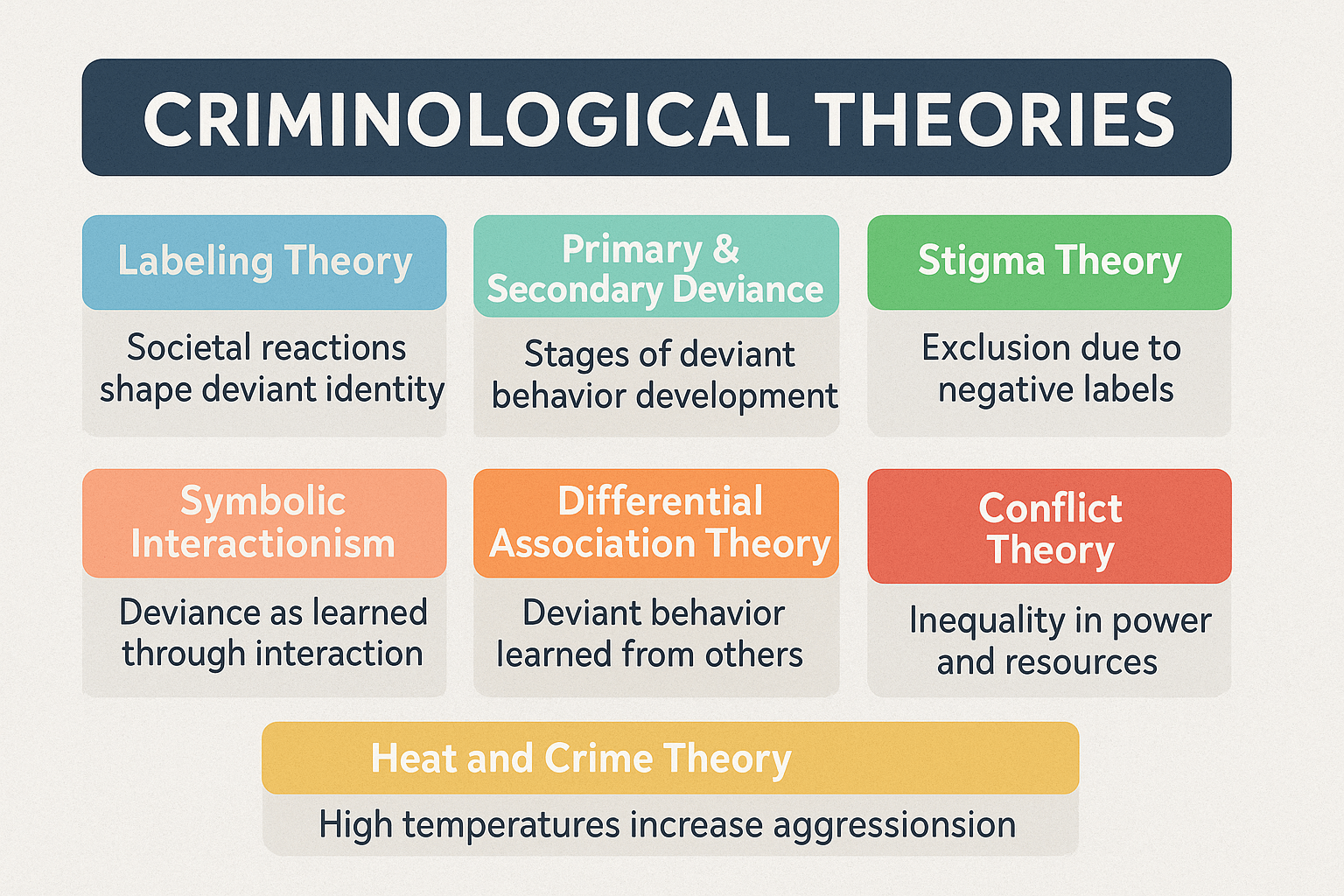

Introduction to Criminological Theories

Criminology is the scientific study of crime and criminal behavior. To understand the nature of crime, criminologists develop theories to explain why individuals engage in criminal acts. These theories encompass a variety of perspectives that focus on factors such as social reactions, psychological processes, environmental influences, and societal structures. In this article, we will explore seven influential criminological theories that contribute to our understanding of criminal behavior. These theories are:

- Labeling Theory

- Primary and Secondary Deviance

- Stigma Theory

- Symbolic Interactionism

- Differential Association Theory

- Conflict Theory

- Heat and Crime Theory

These theories offer essential insights into how crime is perceived and enacted within society. Each theory presents a unique angle on criminal behavior, whether it’s rooted in social interaction, environmental conditions, or societal control.

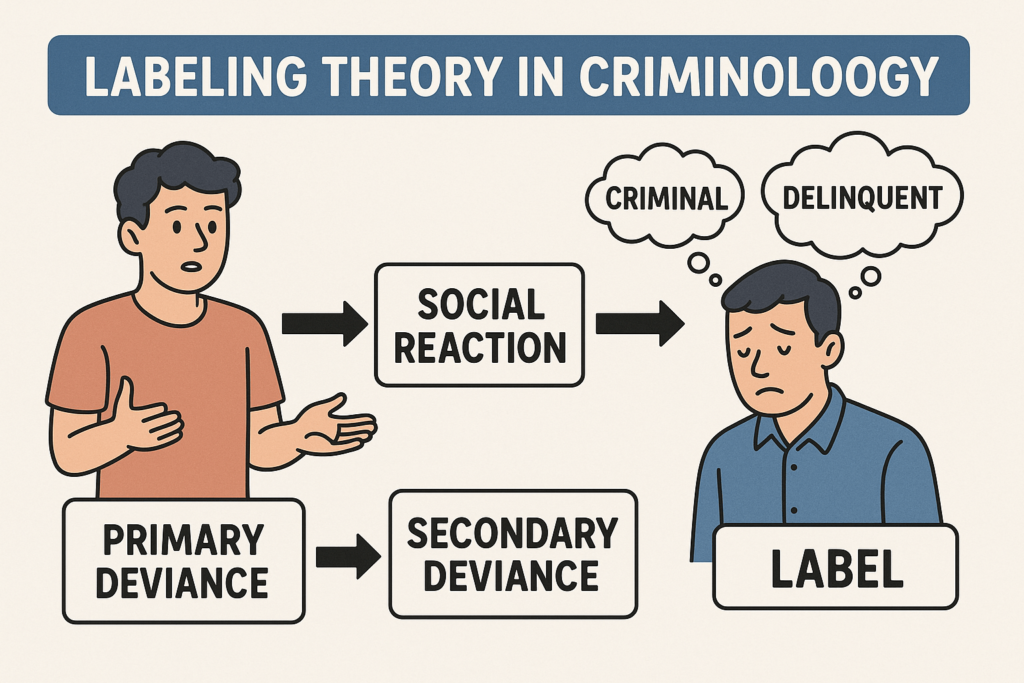

Labeling Theory in Criminology

Labeling Theory suggests that criminal behavior is not inherent in individuals but is the result of the labels applied by society. When a person is labeled as a criminal, society treats them differently, which can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy where the individual internalizes the label and engages in further criminal behavior. This concept was first introduced by Howard Becker in his seminal work “Outsiders” (1963).

Key Concepts of Labeling Theory

- Primary Deviance: Refers to the initial acts of deviance that may be minor or unintentional. These acts often do not result in a significant social reaction.

- Secondary Deviance: Occurs when the individual internalizes the deviant label assigned by society, leading to more severe deviant behavior.

- Self-fulfilling Prophecy: When the label of “criminal” is applied, individuals may begin to act in accordance with this label, reinforcing their deviant identity.

Criticisms of Labeling Theory

While Labeling Theory has been groundbreaking, it has faced criticism for neglecting the initial cause of deviant behavior. Critics argue that the theory does not adequately explain why individuals engage in primary deviance in the first place. Furthermore, not all individuals who are labeled as criminals continue their deviant behavior.

Practical Example

Consider a teenager caught shoplifting. If the teenager is labeled as a “thief” by teachers, peers, and the media, this label may encourage them to adopt a criminal identity. As they internalize this label, they may engage in more serious crimes, thus confirming the societal label.

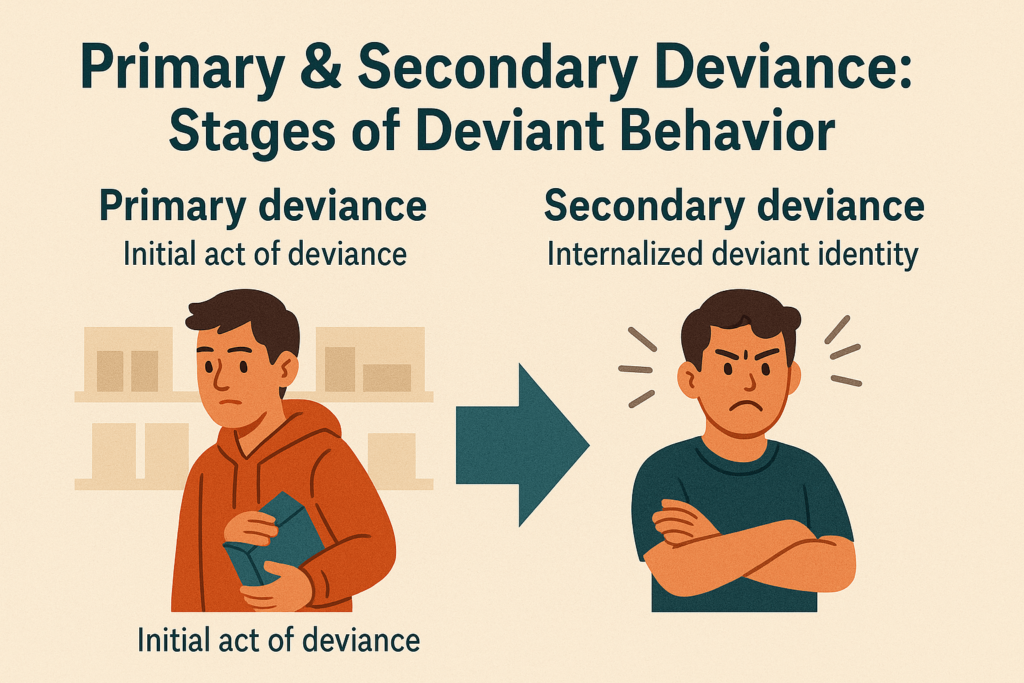

Primary & Secondary Deviance: Stages of Deviant Behavior

Building on Labeling Theory, Edwin Lemert developed the concept of Primary and Secondary Deviance to explain how deviance evolves over time. Primary deviance refers to minor, often unintentional acts of deviance, while secondary deviance refers to more serious deviant behavior that emerges as a result of the individual adopting the label of a deviant person.

Primary Deviance

This stage involves the initial acts of deviance that are not significantly punished by society. These behaviors are often not considered criminal but can set the stage for future deviant acts. Primary deviance can be an isolated act that doesn’t alter the person’s identity. For example, a student skipping class occasionally may not be labeled as a deviant student by peers or society.

Secondary Deviance

Secondary deviance is more serious and occurs when an individual accepts the deviant label and begins to identify with it. At this stage, the person may feel marginalized and excluded from mainstream society, leading to a deeper commitment to deviant behavior. An individual who is arrested for repeated shoplifting may begin to view themselves as a “criminal,” which can perpetuate criminal behavior.

Criticisms

While Lemert’s theory provides valuable insights into the evolution of deviance, critics argue that it oversimplifies the process by which deviant identities are formed. Some studies suggest that individuals do not always internalize labels in the same way, and societal reactions may not always lead to an escalation of deviant behavior.

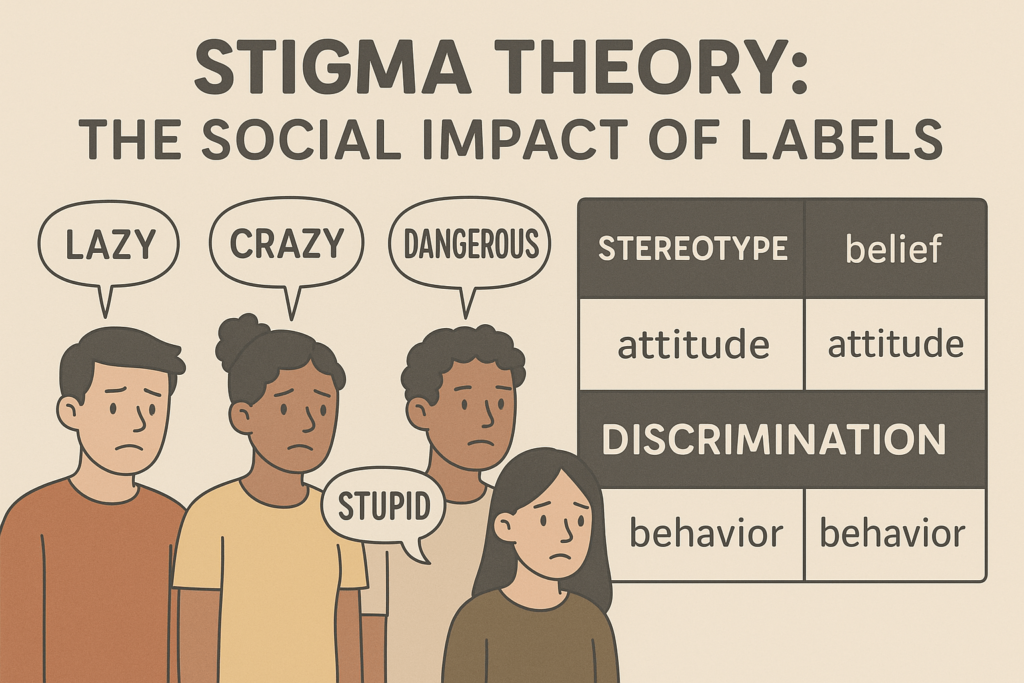

Stigma Theory: The Social Impact of Labels

Stigma Theory, proposed by Erving Goffman, focuses on the negative impact that social labels or stigmas have on individuals. According to Goffman, being labeled as deviant or criminal can lead to social exclusion, discrimination, and marginalization. This theory is particularly important in understanding how societal perceptions of criminals can limit their opportunities for reintegration into society.

Key Concepts of Stigma Theory

- Social Stigma: The mark of disgrace that is attached to certain individuals or behaviors. This label can lead to discrimination and exclusion from societal activities.

- Exclusion: Social stigma often results in exclusion from social networks, employment, and opportunities. This exclusion can reinforce criminal behavior, as individuals may turn to crime as a means of survival or expression.

- Self-Stigma: The internalization of the negative label. Individuals may begin to believe that they are indeed criminals and act accordingly.

Practical Examples

A person who has served time in prison may be stigmatized by society upon release. Even if they want to turn their life around, the stigma associated with their criminal record may make it difficult for them to find a job, leading to a cycle of poverty and reoffending.

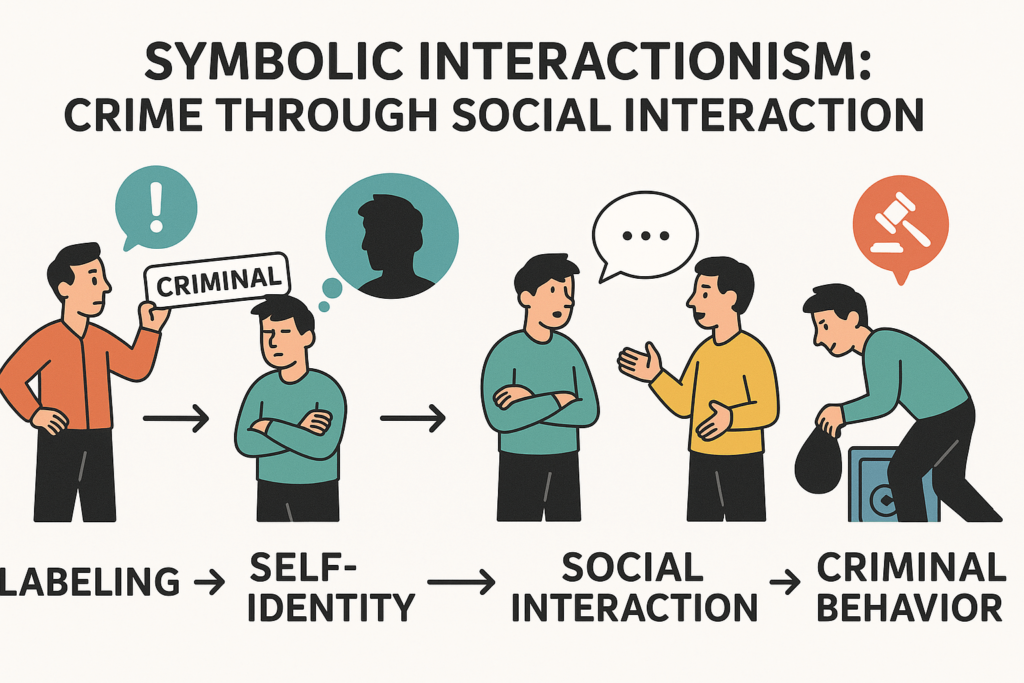

Symbolic Interactionism: Crime Through Social Interaction

Symbolic Interactionism, developed by George H. Mead and Herbert Blumer, suggests that crime is not inherent in individuals, but is learned through social interactions. The theory emphasizes the importance of symbols, language, and meaning-making in the formation of criminal behavior.

Core Principles of Symbolic Interactionism

- Social Interaction: Criminal behavior is learned through interaction with others, particularly those who engage in or condone deviant behavior.

- Meaning of Behavior: Criminal behavior arises from the meaning that individuals assign to their actions. These meanings are shaped through communication and social interaction.

- Role Theory: The roles individuals adopt in society, such as the role of “criminal,” can influence their behavior.

Applications in Criminology

Symbolic Interactionism has been used to explain how individuals come to view themselves as criminals, particularly through interactions with other deviant individuals. For example, a young person who associates with a gang may adopt a criminal identity through continuous social interaction with other gang members.

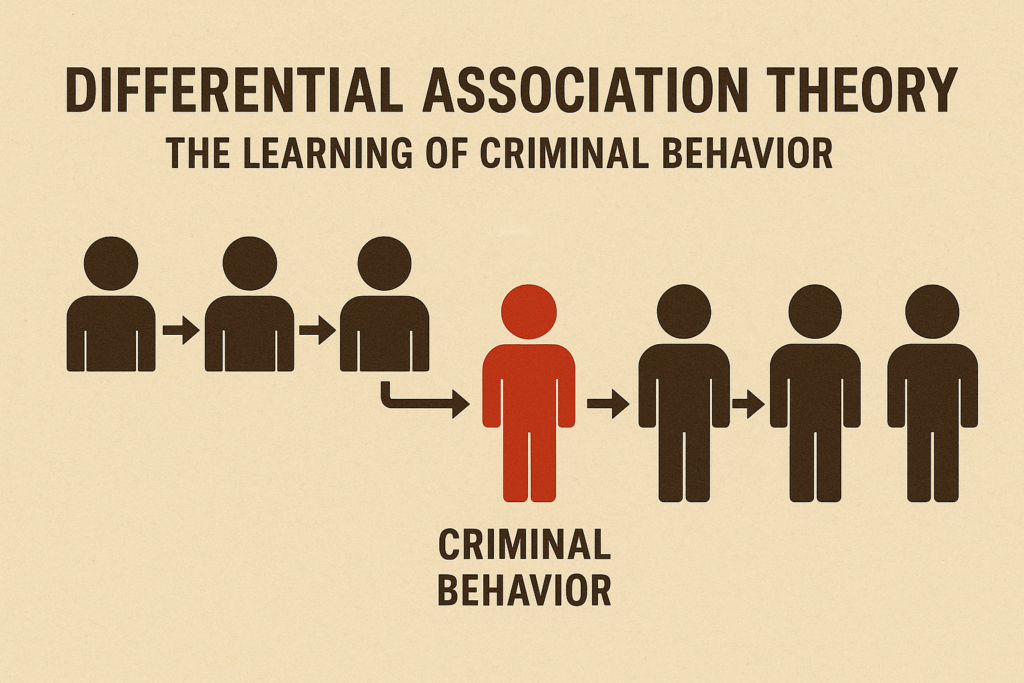

Differential Association Theory: The Learning of Criminal Behavior

Differential Association Theory, proposed by Edwin Sutherland, argues that criminal behavior is learned through association with others who engage in crime. According to Sutherland, crime is not inherited or biologically determined, but is learned through interactions with peers who promote deviant values.

Key Aspects of Differential Association Theory

- Learning Criminal Behavior: Criminal behavior is learned, not inherited. It is learned in the same way as any other behavior, through interactions with others.

- Association with Deviant Peers: The more time an individual spends with people who condone criminal behavior, the more likely they are to engage in crime.

- Frequency, Duration, and Intensity: The likelihood of learning criminal behavior increases based on the frequency, duration, and intensity of the associations with deviant peers.

Practical Example

A teenager who spends time with peers who engage in illegal activities, such as drug dealing, may eventually adopt those behaviors. This learning process is reinforced through shared norms and values that promote criminal behavior.

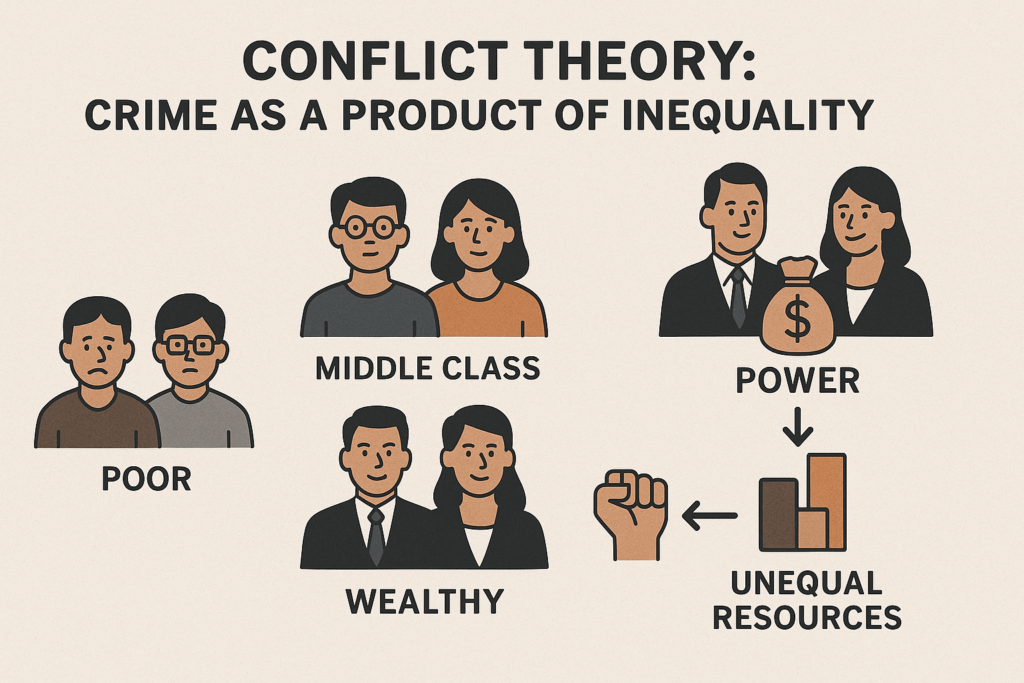

Conflict Theory: Crime as a Product of Inequality

Conflict Theory, associated with Karl Marx and expanded by Richard Quinney, posits that crime is a result of social and economic inequality. According to this theory, the powerful class in society uses laws to control and suppress the powerless, ensuring their own dominance and control over resources.

Key Concepts of Conflict Theory

- Class Conflict: Crime results from the inequality between the upper and lower classes. The wealthy class enforces laws to maintain their position, often at the expense of the marginalized.

- Structural Deviance: Crime can be seen as a product of the social and economic structures that benefit the ruling class while oppressing the disadvantaged.

- Power and Control: The criminal justice system serves the interests of the powerful by criminalizing the actions of the marginalized.

Practical Example

For example, laws that disproportionately target minorities for minor drug offenses may be seen as a tool for maintaining the social hierarchy. Conflict theorists argue that such laws reflect the interests of the powerful class, who seek to maintain control.

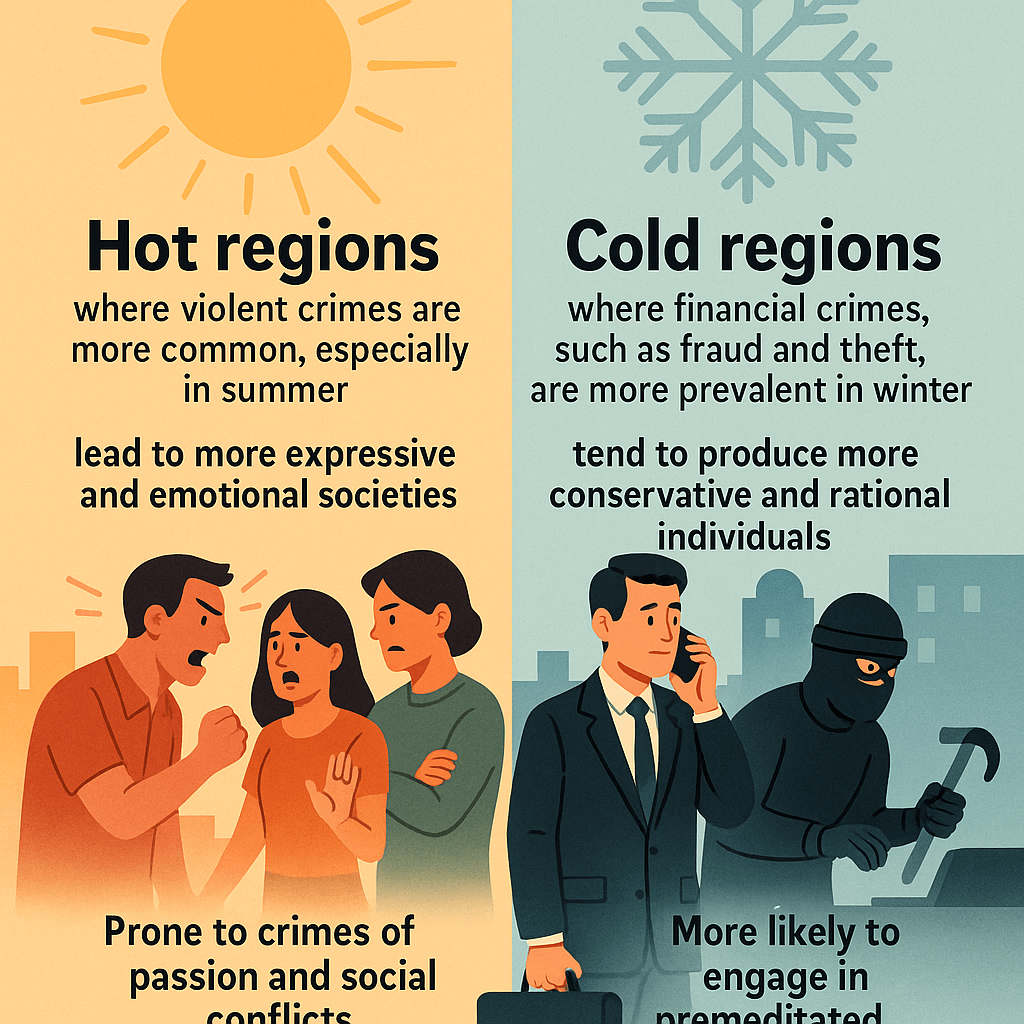

Ibn Khaldun’s Theory of Heat and Crime: Climate and Human Behavior

Ibn Khaldun, the 14th-century Arab historian and social philosopher, proposed one of the earliest theories linking climatic conditions to human behavior. In his famous work The Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun argued that inhabitants of hot climates tend to exhibit impulsive, emotional, and aggressive traits, while those from colder climates develop calmer, more rational, and strategic temperaments.

Climatic Influences on Human Behavior

According to Ibn Khaldun, heat affects not only the physical and moral nature of individuals but also shapes social structures, economic patterns, and even the types of crimes individuals are likely to commit. Ibn Khaldun divided the world into hot and cold regions and suggested that this climatic factor influences human behavior in complex ways:

- Hot regions — where violent crimes are more common, especially in summer — lead to more expressive and emotional societies. These societies are more prone to crimes of passion, such as crimes committed out of anger or jealousy, as well as social conflicts and aggression.

- Cold regions — where financial crimes, such as fraud and theft, are more prevalent in winter — tend to produce more conservative and rational individuals. These individuals are more likely to engage in premeditated crimes, such as white-collar crimes, theft, or fraud, which require planning and calculation.

Connections Between Ibn Khaldun’s Theory and Modern Criminology

Ibn Khaldun’s ideas about the impact of climate on human behavior intersect with many concepts in environmental criminology and social psychology. Studies have shown that there is a correlation between higher temperatures and increased aggressive behavior, known as the temperature–aggression hypothesis. Research indicates that violent crimes, such as assaults and thefts, are more likely to occur during warmer periods, especially in densely populated urban areas.

On the other hand, property crimes, financial fraud, and organized criminal activities are more common in colder climates, where opportunities for premeditated crimes, such as fraud or theft, are more feasible due to the tendency for people to spend more time indoors and engage in long-term planning.

Ibn Khaldun’s Legacy in Modern Criminology

Although Ibn Khaldun’s theory was developed centuries ago, it still has a significant impact on our understanding of the factors influencing crime today. Ibn Khaldun introduced the idea that environmental factors — including climate — can play a major role in shaping both individual behaviors and societal dynamics. While his ideas might appear primitive compared to contemporary criminology, modern research has confirmed several aspects of his theory, solidifying its importance in the development of our understanding of human behavior and crime.

In conclusion, Ibn Khaldun’s theory offers an early environmental criminological model, illustrating how natural elements, such as climate, can influence not only individual behavior but also the moral, legal, and social structures of entire societies.

Comparative Overview of Theories

| Theory | Focus | Key Figures | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labeling Theory | Social reactions, identity | Howard Becker | labeling, deviant identity |

| Primary & Secondary Deviance | Stages of deviance | Edwin Lemert | deviance stages, identity shift |

| Stigma Theory | Discrediting and exclusion | Erving Goffman | social stigma, exclusion, marginalization |

| Symbolic Interactionism | Social interaction, meaning-making | George H. Mead, Herbert Blumer | interpretation, symbols, roles |

| Differential Association Theory | Learned deviance via association | Edwin Sutherland | peer influence, learned criminality |

| Conflict Theory | Power, inequality, systemic control | Karl Marx, Richard Quinney | class conflict, structural deviance |

| Heat and Crime Theory | Environmental triggers for deviance | Craig Anderson, others | temperature, aggression, climate impact |

Conclusion: The Ongoing Relevance of Criminological Theories

Criminological theories serve as powerful tools for understanding the root causes and complex dynamics of criminal behavior within society. By exploring the seven key theories—Labeling Theory, Primary and Secondary Deviance, Stigma Theory, Symbolic Interactionism, Differential Association Theory, Conflict Theory, and Heat and Crime Theory—we uncover a rich and nuanced landscape of explanations that go far beyond individual wrongdoing. These theories highlight the critical roles of social interaction, environmental conditions, peer influence, inequality, and institutional responses in shaping deviant behavior.

Each theory presents a unique lens through which to interpret crime: while Labeling Theory and Stigma Theory focus on how society’s reactions can entrench deviant identities, Conflict Theory underscores how systemic power imbalances and class structures contribute to criminalization. Meanwhile, Differential Association Theory reveals the ways in which deviance is learned through close relationships, and Symbolic Interactionism helps us understand how meaning and social roles are constructed through daily interactions. Even the Heat and Crime Theory, grounded in environmental psychology, reminds us that physical conditions like temperature can influence aggression and criminal behavior.

Together, these perspectives offer an integrated framework for criminal justice professionals, sociologists, psychologists, and policymakers to analyze crime not just as a legal issue, but as a deeply social and structural phenomenon. They also provide crucial insights for reforming legal systems, shaping rehabilitation programs, and addressing the broader social conditions that foster criminality.

As crime continues to evolve in our rapidly changing world—through digital platforms, climate crises, and global inequalities—so too must our understanding. These criminological theories, while rooted in classical thought, remain strikingly relevant today. They challenge us to look beyond surface-level judgments and to critically examine the societal forces that influence behavior. In doing so, we not only expand our academic and professional horizons, but also move closer to building a more just, informed, and empathetic society.

References

- Lemert, E. (1951). Social pathology: A systematic approach to the theory of sociopathic behavior. McGraw-Hill.

URL: https://sk.sagepub.com/ency/edvol/socialtheory/chpt/labeling-theory - Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

URL: https://sk.sagepub.com/ency/edvol/socialtheory/chpt/labeling-theory - Mead, G. H., & Blumer, H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago Press.

URL: https://sk.sagepub.com/ency/edvol/socialtheory/chpt/labeling-theory - Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology. J.B. Lippincott Company.

URL: https://www.simplypsychology.org/differential-association-theory.html - Marx, K., & Quinney, R. (1977). Class, state, and crime. Social Problems, 24(4), 343-358.

URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118517390.wbetc124 - Anderson, C. A., & others. (2000). Heat and violence: The effect of high temperature on violent crime. Crime Science Journal.

URL: https://crimesciencejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40163-022-00179-8 - Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. Free Press.

URL: https://www.britannica.com/topic/labeling-theory